AZTEC WARRIORS/WESTERN SOLDIERS: The Body Politic Feeds Upon Human Bodies

|

Contents

- Aztec warfare: feeding the sun god

- Sacrifice for gods called France, Germany and Great Britain

- The Individual must die so the nation might live

- The body politic feeds upon human bodies

- The Western fantasy of rationality

- The nightmare of history

I. Aztec warfare: feeding the sun god

In our conventional thinking, warfare occurs when one group of people attacks another group of people. We imagine that this attack is occasioned by the perception of a threat to one’s own group, by a desire to conquer or plunder the other group, to obtain revenge for past injustices. People believe that warfare occurs when human beings performing acts of “aggression.”

I propose to reconceptualize the nature and meaning of warfare. Aztec warfare provides a case study. Aztec warfare did revolve around conquest and plunder, but more fundamentally its purpose was to capture warriors from the opposing city-state—in order to sacrifice them.

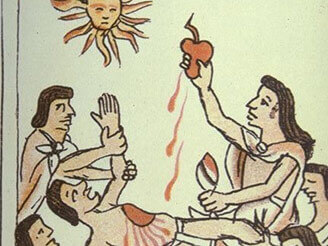

When the Aztecs waged war, they did not try to kill their adversaries. Rather, they captured soldiers and brought them back home to the sacrificial block at the top of a pyramid—where priests cut open their chests, extracted their hearts and offered the warrior’s heart to the sun god.

According to historian Alfredo Lopez Austin (1988), as long as men could offer the blood and hearts of captives taken in combat, the “power of the sun god would not decline”—the sun would “continue on his course above the earth.” To keep the sun moving in its course so that “darkness should not overwhelm the world forever,” anthropologist Jacques Soustelle explains (2002), it was necessary to “feed it every day with its food”—the “precious water,” that is, with human blood.

Unlike the Aztecs, we in the West imagine that wars are fought for “real” reasons or purposes. We understand the death or maiming of soldiers in battle as the by-product— occurring as societies seek to attain practical or political objectives. We do not believe that warfare’s purpose is to produce sacrificial victims, although the result of every war is a multitude of dead soldiers.

II. Sacrifice for gods called France, Germany and Great Britain

In the course of the First World War (1914-1918), approximately 9 million men were killed, 21 million injured, and 8 million captured or reported missing. This war was one of the greatest instances of mass slaughter in the history of the human race. The death toll for one five-month period in 1916—during which the Battles of the Somme Verdun took place—was almost a million men. This represented more than 6,600 men killed every day: 277 every hour, or nearly five each minute.

World War I is famous for the strange way in which battles were fought. Men were asked by the leaders of their nations to get out of trenches and to advance toward the enemy line, where they were met with and torn apart by artillery shells and machine gun fire. In spite of the futility of this strategy, it was never abandoned. The result: four years of perpetual slaughter.

What was going on? Why were leaders willing to continue to push men into battle—and why did young men continue to fight—knowing there was a high probability that they would be killed and a low probability that anything would be accomplished?

We’re dealing with something extraordinary. Historians to this day despair when they attempt to explain the monumental carnage. Joanna Bourke in Dismembering the Male (1996) states that during the First World War the male body was “intended to be mutilated.” How can we comprehend an event—created by human beings—whose primary product was death and the maiming of men’s bodies?

When war was declared in 1914, excited crowds celebrated in every major city. One million volunteers joined the British army during the first year. War Office recruiting stands were inundated with men persuaded of their duty to fight. Soldiers were cheered on as they rushed off to battle.

The First World War cannot be understood apart from peoples’ attachment to entities called “countries.” Leaders, combatants and populaces alike believed that they were acting to defend and preserve their nations. A monumental orgy of destruction was undertaken and justified in the name of regenerating gods called “France”, “Germany”, and “Great Britain”.

Perhaps the Aztec case throws light upon the First World War. British Prime Minister David described the war as a “perpetual, driving force” that “shoveled warm human hearts and bodies by the millions into the furnace.”

III. The individual must die so the nation might live

In the midst of the First World War, nationalist writer Maurice Barrès praised French soldiers (in The Faith of France, 1918) who were dying on a daily basis:

Oh you young men whose value is so much greater than ours! They love life, but even were they dead, France will be rebuilt from their souls. The sublime sun of youth sinks into the sea and becomes the dawn which will hereafter rise again.

Soustelle notes that the Aztecs believed that the warrior who died in battle or upon the stone of sacrifice “brought the sun to life” and became a “companion of the sun.” The rising sun was the “reincarnation of a dead warrior.”

Barrès declared that French soldiers—the “sublime sun of youth”—would sink into the sea to become the dawn that would “rise again.” Just as the Aztecs believed that the bodies and blood of sacrificed warriors kept the sun god alive, so Barrès believed that the French nation would be regenerated based on the bodies and souls of dead soldiers.

According to historian Burr Brundage (1986), Aztec warriors who died or were cremated on the field of battle “spilled their blood on the bosom of mother earth” and then in flames ascended to “enter the sun god’s entourage.” Commenting on the First World War in 1915, P. H. Pearse, founder of the Irish Revolutionary movement, gushed that the previous 16 months had been the “most glorious in the history of Europe.” The earth, he said, needed to be “warmed with the red wine of the battlefields.” He described the carnage as an offering to God: millions of lives “given gladly for love of country.”

The First World War was undertaken, justified and perpetuated in the name of countries. The assumption seems to have been that the “lives” of nations were more significant than the lives of human beings. Germany, France and Great Britain were fed with the bodies and blood of soldiers—sacrificial victims—in order to keep these entities alive.

“The individual must die so that the nation might live” has been uttered throughout the history of modern warfare. But what does this proposition mean? The First World War represented an extraordinary enactment of this idea or fantasy: the nation was imagined to come alive insofar as it was fed with the bodies and blood of sacrificed soldiers. Warfare represented the enactment of a fantasy of death and resurrection.

IV. The body politic feeds upon human bodies

Based on analysis of the letters of French soldiers who fought in the First World War, historian John Horne (in Coetze and Shevin-Coetze, 1995) found that the central theme running through them was the idea of national sacrifice as a source of redemption and renewal.

Shortly before his death, Robert Dubarle wrote of the glorious privilege of “sacrificing oneself, voluntarily.” Looking at the warriors who had fallen around him, French soldier J. Saleilles wondered whether the “gift of their blood” was not the supernatural source of the “renewal of life that must be given to our country.”

F. Belmont—moved by attending a field mass with 500 soldiers—wrote that the war, like all great sacrifices “at least has a purifying role.” It was by virtue of sacrifice and suffering that regeneration occurred. A Catholic priest serving as an ambulance man on the Western Front expressed a similar vision: “We await the decisive all-out assault. So many sacrifices! May they help bring the resurrection of a greater, more beautiful and truly Christian France.”

Whence came this conviction that dead soldiers constituted the “supernatural source” of the renewal of the life of France? Why would the sacrifice and suffering of French soldiers bring about the regeneration of France? What logic connects redemption of a nation to the death of its soldiers?

Perhaps the metaphor of the soldier’s death as a “gift of love” provides a clue. This metaphor conveys the idea of death in battle as a transfusion—the moment at which blood contained within the body of the soldier passes or flows into the body politic—functioning to energize the latter and keep it alive.

The Aztecs believed that the hearts and blood of sacrificial victims were required in order to keep the sun god alive. What sustained the First World War was belief that the hearts and blood of soldiers were required to keep nations alive. The First World War represented the enactment of a massive, sacrificial fantasy.

This fantasy of sacrifice builds upon the idea that nations are actual, concrete entities: real “bodies politic.” To keep these entities—bodies politic—alive, they must be fed with human bodies. Just as the Aztec sun god continued to exist only insofar as it was fed with sacrificial victims, so nations continue to exist to the extent that soldiers die in their name. The body politic feeds upon human bodies.

V. The Western fantasy of rationality

Most of us find the Aztec ritual of heart extraction bizarre, shocking and painful to contemplate. Yet we barely reflect upon our own suicidal political rituals, such as the First World War. Western people believe they are superior to the “primitive” Aztecs. However, the Aztecs were not unaware of the sacrificial purpose of warfare.

Western people live deeply within another fantasy: that human behavior is governed by “rationality.” We imagine that societies wage war for “real” reasons. We desperately cling to this fantasy despite what actually occurred during the 20th Century—in which 200 million people died as a result of political conflicts generated by states, producing little in the way of substantial, meaningful or positive results.

A central theme of the 20th century was massive, collective acts of destruction performed by nation-states. The irrationality of these episodes of mass slaughter stares us in the face. Yet social science continues to be dominated by the idea that political acts are undertaken in the name of achieving “real” goals or objectives.

In the 20th century, Western people undertook acts of warfare and genocide—sacrificing human beings on a scale that would have been unimaginable even to the Aztecs. Yet we are not yet aware—are unwilling to acknowledge—that we have been enacting massive rituals of sacrifice.

VI. Awakening from the nightmare

The ideal of “awakening from the nightmare of history” builds on the hypothesis that when human beings enter the domain of politics, they are living within a dream. To this day—as you read this—people continue to blow each other up in the name of nations, gods and ideologies.

Infantryman Coningsby Dawson fought in the First World War and published two books in 1917 and 1918, seeking to convey the experience and motives of his fellow British soldiers. These men, he said—in the “noble indignation of a great ideal”—face a worse hell than the “most ingenious of fanatics ever planned or plotted.”

Dawson described some of the horrific scenes he witnessed. Men, he wrote, die “scorched like moths in a furnace, blown to atoms, gassed, tortured.” Yet the carnage continued because, while some men perished, other men stepped forward to take their places “well knowing” what their fate would be.

What was the source of this willingness of men to die? Dawson claims that it was precisely for the sake of Great Britain, proudly proclaiming that although “bodies may die,” the spirit of England “grows greater as each new soul speeds upon its way.” Dawson, in short, posits a correlation between the death of British soldiers and the soul of the Empire.

With the death of each soldier, the spirit of England grew greater. Changing one word in this passage crystallizes the logic linking the death of soldiers to the growth of one’s nation: “Bodies may die—therefore the spirit of England grows greater as each new soul speeds upon its way.” A mathematical formula is suggested: one’s nation grows in proportion to the number of men who have died in its name.

The nightmare of history derives from the fantasy that human beings exist in a symbiotic tie to—cannot be separated from—their nations. Rudolf Hess often introduced his Fuehrer by declaring, “Hitler is Germany, just as Germany is Hitler.” This is not an unusual idea. Many human beings identify—link their identities—with their nations.

People conceive of their nation as an omnipotent entity with which their self is fused. Human beings equate their own bodies with a body politic. In the name of devotion to nations or bodies politic, societies are willing to sacrifice the lives of actual human bodies.

What would it mean to awaken from the nightmare of history? The first step is to recognize that we live within a waking dream. This dream—this collective fantasy—centers around the idea that lives must be sacrificed in order to keep nations alive.