“Strengthening Cultural War Studies”

Introduction to Culture, Trauma and Conflict: Cultural Studies Perspectives on War (Cambridge Scholars Publishing)

by Nico Carpentier

The Ideological Model of War

War, i. e. armed conflict between organized political groups, is still an omnipresent phenomenon. In the meantime, though, despite the fact it has been “the universal norm in human history” (Michael Howard 2001, 1), its highly disruptive and destructive nature has strongly decreased its social respectability and acceptability.

Howard (2001, 2) stresses the relative novelty of this development: “the peace invented by the thinkers of the Enlightenment, an international order in which war plays no part, had been a common enough aspiration for visionaries throughout history, but it has been regarded by political leaders as a practical or indeed desirable goal only during the past two hundred years. ”

Despite a theoretical and ethical consensus surrounding the desirability of structural peace, its implementation has proven difficult—witness the high number and horrible intensity of armed conflicts and genocides in the 20th and 21st centuries. The principled repulsion of war seems to become easily translated into a discourse about the acceptability of war in the last instance. It is precisely this paradox between the consensus surrounding the desirability of structural peace and the apparent unavoidability of armed conflict that legitimizes its continued analysis.

The deep societal impact of war further strengthens this legitimization. This impact is partially related to the actions of the soldiers (or fighters) involved, engaging in what Joanna Bourke (1999, 1) calls “sanctioned blood-letting, ” supported by processes of hero making. Her _Intimate history of killing—_despite the growing distance between killer and killed—points to the problematic “association of pleasure with killing and cruelty” (Bourke 1999, 369).

The societal impact is not restricted to (semi-)military personnel; entire nations become symbolically engaged in this process of de-civilization. The loss of humanity is not confined to the actual battlefield sites; war tends to cannibalize on the social and absorb it. War touches the core of our politics, economics and cultures. The threat to the survival of the state and its citizens (and soldiers) creates the political legitimacy, and the political will to revert to extreme and counter-democratic means in order to reach the ultimate goal of winning the war. Truth is not necessarily the only “first casualty of war”.

As Aeschylus put it, the suspension of democracy and human rights often follows quite rapidly. In the War and the media collection, Aijaz Ahmad (2005, 22) for instance points to what he calls the domestic dimension of the “war on terrorism”, which takes surveillance “to new extremes in an otherwise democratic country. ” In addition, the economic and financial structure of a nation is affected. During wartime, and especially during prolonged periods of conflict, the importance of the already important industrial-military complex increases–weighing heavily on the public purse.

And finally, war affects the cultures of the warring parties. The edges of imagined communities at war, which are blurred in more normal circumstances, become impenetrable frontiers between “us” and “them”, between the Self and the Enemy. All eyes become strongly focused on the (political) center, and citizen-soldiers voluntarily subject themselves to the leadership of a small political-military elite.

There is little room for internal differences, as illustrated in the famous words of the German Emperor Wilhelm, in claiming during the First World War that he no longer wanted to hear of different political parties, only of Germans. U. S. President, George Bush, used an updated version of this dictum in his address to the Joint Session of Congress and the American People on September 20, 2001, when he said: “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists. ” And an inversed version was used by Russian president Vladimir Putin, who stated in his Crimea address on 18 March 2014:

They act as they please: here and there, they use force against sovereign states, building coalitions based on the principle ‘If you are not with us, you are against us. ’ To make this aggression look legitimate, they force the necessary resolutions from international organizations, and if for some reason this does not work, they simply ignore the UN Security Council and the UN overall.

These three examples show the crucial role that ideology—defined as sets of ideas that dominate a social formation—plays in generating internal cohesion and in turning an adversary into the Enemy. This transformation is supported by a set of discourses, articulating the identities of all parties involved. Together they form an ideological model that has structured most of the interstate wars[1] in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Although each war has its own history and context which makes it unique, wars are nevertheless built on remarkably similar ideological mappings. So, on the one hand, the complex series of events that compose a war appear to be highly elusive and impossible to represent in their entirety; but on the other hand, the core ideological models that have structured wars in past decades tend to be fairly stable and compatible.

This ideological model of war is crucial to understanding modern warfare, as its core structure allows us to better understand (and counteract) the discourses, rhetorics and narrations of war. As Keen (1986, 10) put it: “in the beginning we create the enemy. Before the weapon comes the image. We think others to death and then invent the battle-axe or the ballistic missiles with which to actually kill them. ”

This of course does not imply that the processes of mediation and representation completely overtake the practices and materiality of war (and of killing). But in the (20th and) 21st century, interstate war in particular has become a political transgression which requires a discursive build-up to legitimize the use of extreme military violence, all of which makes it necessary to (re)construct this ideological model of war.

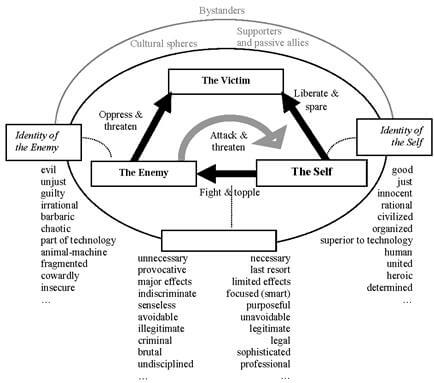

For this (re)construction, we first turn to Galtung (see, for instance, Galtung and Vincent 1992) who, from a Peace Studies perspective, has pointed to the dichotomized nature of these discourses, grounded by the key binary opposition of good and evil. The variations of the good/evil dichotomy that structure the identities of both Self and Enemy are manifold: just/unjust, innocent/guilty, rational/irrational, civilized/barbaric, organized/chaotic, superior to technology/part of technology, human/animal-machine[2], united/fragmented, heroic/cowardly and determined/insecure.

A second layer of dichotomies structures the meanings attributed to the violent practices of both warring parties. These dichotomies include, among others: necessary/unnecessary, last resort/provocative, limited effects/major effects, focused/indiscriminate, purposeful/senseless, unavoidable/avoidable, legitimate/illegitimate, legal/criminal, sophisticated/brutal and professional/undisciplined.

The dichotomies in question can be defined as floating signifiers (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 112-113; Žižek 1989, 97), implying that these signifiers have no fixed meaning but are (re)articulated before, during and after the conflict and inserted into different chains of equivalence.

At the same time, the dichotomies play a key role as nodal points in hegemonic projects, where they have become fixed (being attributed with specific meanings) and are used to fix a wide variety of other discursive elements. In short, both sides claim to be rational and civilized and to be fighting a good and just war, laying responsibility for the conflict on the Enemy.

Both sides present their violent practices as focused, well-considered, purposeful, unavoidable, and necessary. Both sides construct their own (inversed[3]) ideological model of war.

The construction of the Enemy is accompanied by the construction of the identity of the Self as clearly antagonistic to the Enemy’s identity. In this process, not only is the radical otherness of the Enemy emphasized, but also the Enemy is presented as a threat to “our own” identity. Ironically, the identity of the Enemy as a constitutive outside is indispensable to the construction of the identity of the Self, as the evilness of the Enemy is a necessary condition for the articulation of the goodness of the Self.

Apart from the identities of the Self and the Enemy, there is a third discursive position—that of the Victim—which is crucial to the ideological model of war. Here it is important to keep LaCapra’s (723) words in mind: “‘Victim’ is not a psychological category. It is, in variable ways, a social, political, and ethical category. ”

The identity of the Victim may range from abstract notions, such as world peace or world security, to more concrete notions, such as a people, a minority, or another nation. In some cases the Self becomes conflated with the Victim, for instance when the Self is being attacked by the Enemy. For instance, in the case of the Cyprus conflict, where Turkey invaded the island in 1974 and occupied more than one third of the island’s territory, the Greek Cypriot Self is often articulated as Victim of this invasion.

In contrast, the Turkish Cypriot Self is frequently defined as Victim of the intra-communal violence of the 1960s (and before). Papadakis’ (2006, 78) analysis of the material produced by the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Public Information Offices shows that these documents produced by both sides “literally screamed with pain. Their aim was to show who truly suffered, who suffered most, and who was to blame for this suffering. ”

In other instances the Victim is detached from the Enemy, when a regime is seen to (preferably brutally) oppress its “own” people, or when in intra-state or civil wars the nation or people become divided into warring factions. An example here is the 2003 Iraqi War[4], where the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein and the ruling Ba’ath party was defined as victimizing the Iraqi people (and especially the Shiites and Kurds), and was simultaneously seen as a threat to world security because of its alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) (see Carpentier 2007).

The Victim is intrinsically linked to the identity of the Self and the Enemy, as its being victimized contributes to the construction of the evilness of the Enemy. The Self’s goodness emanates not only from the willingness to fight this evilness, but also from the attempts to rescue the Victim. These three discursive positions—Self, Enemy and Victim—together form the core structure of the ideological model of war rendered in Figure 1-1. In this model, the Self and the Enemy are juxtaposed, and encircled by the dichotomies that structure their identities in an intimate relationship with the Victim.

Somewhat in the background, this model also contains the discursive positions of Supporters and Passive Allies, which belong to a similar cultural sphere and tend to reproduce (at least partially) the constructions of the identity of the Self and Enemy. Finally, Bystanders have no direct affiliations to the conflict or the warring parties and relate to the conflict from their own particular contexts, which do not necessarily include the identity constructions of the Self and Enemy (as produced by the Self).

Figure 1-1: The ideological model of war

Of course, it should be kept in mind that these positions are discursive- ideological constructs, with an always-specific relationship to the complex mixture of events and practices, offering overarching frameworks of interpretation without which materiality remains unintelligible, but never able to capture the richness of these events and practices in their entirety.

Following De Certeau’s (1992) argument in The Writing of History and Laclau’s (1996) argument in Emancipations, the unavoidable particularity of discursive translations needs to be emphasized. Moreover, the ideological model depicted in Figure 1-1 cannot be considered as being stable or fixed during (or before and after) war. From a Foucauldian perspective, it needs to be seen as the unstable overall discursive effect of a wide range of societal strategies aiming to define the Enemy and the Self.

Although these ideological models of war are supported by hegemonic projects (of the state and/or the warring parties), different forms of resistance (outside as well as inside governments) permanently attempt to rearticulate them. Furthermore, the stream of events generated by the war could in many cases—often with the support of propaganda—become incorporated into the model, whereas other events require the model to be rearticulated. In extreme cases, events might even threaten the structural integrity of the ideological model.

An example of such an extreme event is the Tet offensive during the Vietnam War, which severely crippled the Vietcong at the military level, and at the same time totally disrupted the U. S. ideological framework (see Hallin 1986). Within the discourse-theoretical frame, the term dislocation is used to refer to such moments of crisis.

A dislocation can be defined as the destabilization of a discourse by events it is unable to integrate, domesticate or symbolize. Dislocations disrupt discourses and identities, but at the same time become the breeding ground for the creation of new identities (Laclau 1990, 39). Moreover, they bring to light the contingency of the social and, in doing so, become “the very form of temporality, possibility and freedom” (Laclau 1990, 41-43, summarized by Torfing 1999, 149).

Although the ideological model of war that constructs the identities of the Self and the Enemy is widespread, specific groups of actors tend to play a vital role in the hegemonization of this model. These groups may benefit from unequal power relations that increase the weight of their statements.

A first group of actors is usually referred to as the state, and includes governments, parliaments, political parties, advisory bodies and, last but not least, the military. The state often holds decision-making powers, has to assume responsibility for waging the war, and is held accountable for the course of the war. However, its political function of representing and governing “the people” means that its statements (and actions) are also essential for establishing or supporting a hegemonic process.

As war is considered to be a very specific condition, threatening the existence of numerous human beings and possibly even the survival of the state itself, it is not sufficient to legitimate the war as such. Next to military victory, mobilization of support from the “home front” (national unity) is a primary political objective legitimating hegemonic policies.

In addition to censorship, which aims to restrict the circulation of discourses, an instrument that is widely used for the purpose of hegemonization is, of course, propaganda. Characteristically, it is planned by organized groups, which can range from a small number of special advisors to large bureaucratic organizations responsible for propaganda and counter-propaganda efforts (Taylor 1995, 6; Jowett 1997, 75).

This distinguishes it from hegemony, which is the relatively rigid but ultimately unstable result of a negotiative societal process determining the horizon of our thought within a specific social and temporal setting. Although propaganda can be instrumental in establishing hegemony, the societal construction of the collective will to fight a war transcends all propaganda efforts.

When attempting to further define propaganda, the parallel with ideology—again a much broader notion—is helpful. The traditional (rather negative) Marxist definition of ideology as false consciousness runs in parallel with the common sense view of propaganda as untruthful. Taithe and Thornton (1999, 1) describe this view as follows: “most readers will assume that [propaganda] is largely composed of lies and deceits and that propagandists are ultimately manipulators and corrupt. ”

More neutral definitions of ideology as a set of ideas that dominate a social formation, allow for an approach that defines propaganda as a persuasive act with a more complex relationship towards truthfulness (Ellul 1973). Along similar lines, Taylor (1995) defines propaganda as the use of communication “to convey a message, an idea, an ideology … that is designed primarily to serve the self-interests of the person or people doing the communicating. ”

Mediated Representations of War

One of the major targets of the state’s propaganda efforts is the mainstream media, which—as Kellner (1992, 57) remarks—should not be defined as hypodermic needles, but as “a crucial site of hegemony. ” A wide range of information management techniques has been developed in order to influence the (news) media’s output. However, this is not to imply that the mainstream media are defenseless victims.

Here, the media’s specificity should be taken into account, both at the organizational level and at the level of media professionals’ identities. The majority of the (Western) media can be seen as relatively independent organizations, with specific objectives and specific values.

Even the most liberal normative media theories focus on the obligation of mainstream (news) media to independently inform their audiences and to use that independence to subject state practices to public scrutiny. Moreover, media professionals claim to have access to the description of factuality and to represent truth or authenticity, which potentially runs counter to (some of) the propaganda efforts of the states at war.

Unfortunately, this does imply that media organizations and media professionals can easily escape from the workings of the ideological model of war. Although both like to believe that they are outside the operations of ideology—what Schlesinger (1987) has called the macro-myth of independence—ideology as such, and the workings of the ideological model of war, are difficult to escape.

A first point to be made here is that journalism is itself a professional ideology, as argued, for instance, by Deuze (2005) and Carpentier (2005). Secondly, ideology penetrates the representations that media professionals generate. If the discourses on the Enemy and the Self have been hegemonized and turned into common sense, they may become the all-pervasive interpretative frameworks of media professionals.

At the same time, care should be taken not homogenize the diversity of media organizations and practices. In a number of cases the mainstream media have managed to produce counter-hegemonic discourses. They have provided spaces for critical debate, in-depth analysis and humor. They have also attempted to counter some of the basic premises of the ideological model, and tried to show the horror of war.

The mainstream media are not the only discursive machinery to attribute meaning to war. Other spheres, such as literature, the arts, the streets (as public spaces), film, cartoons, and popular culture, contain discourses that reproduce or disrupt the hegemonic discourses of war.

An almost visionary example of the critical capacity of popular (music) culture can be found in George Michael’s pop song and video clip Shoot the Dog, which was released before the onset of the 2003 Iraqi War. It contained a (rather amusing) critique of the dependent relationship of Britain with the U. S. A. , depicting Tony Blair as Bush’s puppy, thus attempting to disarticulate the homogeneous Western Self.

In a statement about this song, George Michael made an explicit reference to the impending war in Iraq, when he posed the following question:

I have a question for you, Mr. Blair. On an issue as enormous as the possible bombing of Iraq, how can you represent us when you haven’t asked us what we think. And let’s be honest, we haven’t even begun to discuss it as a society. So please Tony, much as we’ve all loved watching the best team we’ve had in 40 years at the World Cup, and much as we loved the Jubilee, now that we have some downtime, could we have a little chat about Saddam? (Michael 2002)

Recognizing Pain, Memory and Trauma

The focus on ideology and representation has no ambition to ignore the materiality of war. War impacts on human bodies with almost unimaginable force. It destroys or mutilates them. It causes pain to them, and traumatizes them.

The (individual) trauma is not only physical, but also psychological, well exemplified in the phenomenon of shell shock. Erikson (1976, 153) defines this individual trauma as “a blow to the psyche that breaks through one’s defenses so suddenly and with such brutal forces that one cannot react to it efficiently. ”

But the impact of war does not end here. War does not start with the onset of actual hostilities. First the Enemy-Other needs to be created, which in principle requires painful detachment of that Enemy from the global Self (in other words from humanity), and in which ideology provides the anesthesia that blocks the pain of detachment.

But this preparation also has a material component. Preparing for war requires a specific mindset, which is generated through a series of rituals. For soldiers this is achieved through military training, but civilians also engage in the performance of “homeland security” rituals.

Such (self-) disciplining practices are strongly reminiscent of Foucault’s (1978) descriptions in Discipline and Punish, as the rituals involved act directly on the bodies of the soldiers and the civilians. The soldiers in particular are molded to become the docile killing bodies that will carry out the actual elimination of the Enemy.

War does not end when hostilities cease. The damaged and mutilated bodies remain. Memories of the disappeared bodies also remain, in some cases fed by institutionalized hope, as with the Cypriot Missing Persons (Sant Cassia 2005). And the traumatic memories of war remain.

War is a dislocation that disrupts social and cultural structures, and that continues to do so after the violence ends. It is “a blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together and impairs the prevailing sense of communality” (Erikson 1976, 153).

War trauma is more than the aggregation of individual traumata. It is collective, a “‘knot’ tying together representation, the past, the self, the political and suffering” (Buelens, Durrant and Eaglestone 2014, 4), that continues to structure a culture, for generations and decades, in many predictable and unpredictable ways.

At the same time the harrowing memory of war forces us back to questions of ideology and representation. However hard our cultures try to materialize memory by enshrining it in memorials, museums, and other sites of memory, our representations are unavoidably all that we are left with.

To use Eyerman’s (2001, 12) words: “how an event is remembered is intimately entwined with how it is represented. ” As direct access to (past or present) events is a realist illusion, the discursive mediation of those events becomes a condition of possibility for their continued existence within a society or a culture.

De Certeau’s (1992) argument highlights the discursive-ideological struggle (or, to use Hall’s phrase: “the struggle to signify”) that lies behind these representational processes, in which the ideological model of war often prevails. The meaning attributed to events is not stable, but the result of a process of cultural negotiation. Although its hegemonic truths are protected, contestation and attempted renegotiations always remain possible.

This process of memorialization also implies forgetting. Historical knowledge creates a narrative of a series of events and attempts to mold the infinite details of people’s lives (and deaths) into a systematic discourse, often reducing those lives to “causes, politics, leaders and results” (Lewis 2002, 270).

Moreover, the processes of glorification of the Self and demonization of the Enemy are by default used to make sense of the loss, which also impacts on what is remembered and what is forgotten. Forty and Küchler (1999, 9) for instance refer to the commemorative activities that took place after the First World War.

Their specific aesthetics and conventions were “in some people’s view, a most misleading view of the war that had just been fought. ” Forty and Küchler add: “But it is surely an inevitable feature of memorials … that they permit only certain things to be remembered, and by exclusion cause others to be forgotten. ” Again, ideology plays a crucial role in this process of memorializing and forgetting.

Strengthening Cultural War Studies

The above discussion contains an (implicit) plea for recognition of the importance of ideology, representation, identity, pain, trauma, and power as analytic categories for War Studies. The importance of these concepts has increased markedly in the last decade—enough for Griffith (2001) to proclaim the cultural turn in (Cold) War Studies. But there continues to be a series of problems.

Early versions of Cultural War Studies have not managed to permeate traditional War Studies, leading to a continued underestimation of the importance of these analytic categories in “mainstream” War Studies, and in a number of its subfields.

Moreover, Cultural War Studies still has difficulties in defragmenting itself into a critical and fairly coherent—but open and interdisciplinary—subfield of War Studies, or of Cultural Studies. Establishing Cultural War Studies as a separate discipline would of course be self-defeating—a discipline would be too disciplining for any strand of Cultural Studies—but the nomadic nature of Cultural War Studies has prevented it from exerting much influence on either War Studies or Cultural Studies.

War Studies has become a vast field of study, and a diversity of academic subfields has produced an extensive collection of articles, readers and monographs on the issues of war and conflict. Not only have scholars working in the fields of History, Political Studies and International Relations contributed to this body of literature, but Media, Journalism and Communication Studies scholars also have contributed to long lists of publications, while Propaganda Studies has produced an equally extensive set of publications.

Although Propaganda, Media, Journalism and Communication Studies may seem promising for an approach to ideological processes, most of this literature is fairly traditional—albeit sometimes very critical—for instance, in analyses of the problems that journalists have to face when dealing with the military, the difficult relationships between media organizations and the military, and the way that propaganda affects media coverage.

Of course, and fortunately, there are exceptions in this subfield that do place a stronger emphasis on ideology, representation and (popular) culture and, more generally, on the relationship between ideology, culture and conflict. But this list is much smaller. Examples that come to mind are War, culture and the media. Representations of the military in 20th century Britain (Stewart and Carruthers 1996); Fighting fictions. War, narrative and national identity (Foster 1999), Watching Babylon.

The war in Iraq and global visual culture (Mirzoeff 2005) and Monsters in the Mirror: Representations of Nazism in Post-war Popular Culture (Buttsworth and Abbenhuis 2010). Other examples, from the subfield of Holocaust Studies, are Narrating the Holocaust (Reiter 2000); Visual culture and the Holocaust (Zelizer 2001), Holocaust and the moving image (Haggith and Newman 2005) and The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (Hirsch 2012).

As Jeffords (2007, 238) remarks, also militarism is an area of Cultural Studies production, because it refers to “the complex set of social, political, economic, and cultural activities and institutions that support a society that engages in warfare. ”

And of course, there are authors that defy any classification, such as Paul Virilio (1989; 2002), Jean Baudrillard (1995), Slavoj Žižek (2002; 2004), Susan Sontag (2003) and Judith Butler (2009), who have published work on the role of specific cultural systems in war, such as cinema, the media, and photography. Nevertheless, the attention to ideology and representation in Propaganda, Media, Journalism and Communication Studies is still fairly new and limited, and the culturalist analyses are far from being all-pervasive.

Thus, although it might be too early to claim that the existence of a cultural turn can be expanded to War Studies in general, and it is definitely still too early to refer to an ideological turn in War Studies, Cultural Studies certainly has the potential to fill this gap. It has always exhibited a strong interest in the role that power, ideology and hegemony play in our contemporary conjuncture.

Even in the early days of Cultural Studies, exemplified by Policing the crisis (Hall et al. 1978), it aimed to critically address the power imbalances in society, and the ways that ideology contributed to the maintenance of these imbalances and to the (self)disciplining of the members of these societies.

Arguably, the critical project of Cultural Studies was even strengthened by its generating an opening for polysemy and agency to enter the stage, allowing a move beyond the subject theory of the powerless. Also, Cultural Studies has had a continuing intimate relationship with the concepts of identity, representation, othering and power (see Hall 1997) which makes it extremely suited to providing an ideological angle to War Studies, focusing on the representations that support the ideologies of war and the identities of the Self and the Enemy.

Again, Cultural Studies has contributed strongly to the articulation of the concept of representation as part of the critical toolkit, and to revealing the sometimes problematic nature of our ways of seeing and thinking of ourselves and others, for instance in relation to gender, class, and ethnicity.

As already mentioned, a number of authors have published on war from a Cultural Studies perspective, and many more will undoubtedly do so. Also, a number of structuring initiatives have been taken, for instance through the establishment of the working group on Culture and War of the Cultural Studies Association (U. S. ) and the Journal of War and Culture Studies.

But given the societal and cultural impact of war, such initiatives are relatively few, and they have not managed to push ideology and representation to a higher position on the general War Studies research agenda. This generates an interesting paradox: traditional War Studies scholarship has neglected ideology and representation, and also in the fields that might overcome this shortcoming, none has managed to do so (yet).

One can speculate about the nature of this deficiency. One can look at the disinterest of the more traditional strands of academia in the Cultural Studies apparatus, and their preference for historical realities and factuality. One can look at Cultural Studies itself and carefully suggest the following explanations: the loss of popularity of the concept of ideology in Cultural Studies; its difficulties in looking beyond specific and localized imagined communities, and the conflation of Cultural Studies and the Study of Culture.

Without showing much intellectual creativity, one can even blame the more celebratory strands in Cultural Studies that seek out audience agencies. A more positive approach to addressing this deficiency would be to call for a strengthening of Cultural War Studies5.

War was pervasive in the 20th century, and so far the 21st century seems to hold little promise of improvement. War is still one of the world’s most destructive forces, which on a daily basis touches the lives of millions of people: those who have lived through war (and continue to mourn the losses it has brought), those currently living the war, and those that will live a war still to come.

The societal presence of what Knightly (1982) calls “the institution of war” is thus structural, in that it requires all possible perspectives to be put to work to increase our understanding of this pervasiveness and destructiveness, of this eternal repetition of the same. Cultural War Studies has an important role to play in adding to this knowledge, by putting the critical vocabulary (including ideology, representation, and power) of Cultural Studies to good use to analyze the constructions that push us towards a glorified killing of our fellow (wo)men and then try to make us forget the intensity and durability of the trauma.

At the same time a strengthened Cultural War Studies would contribute to Cultural Studies by putting ideology more firmly on its research agenda, and by sharpening its critical objectives. Cultural Studies should be more than a project that combines eloquent textual readings, in-depth analyses of (preferably resistant) consumption practices and a celebration of human agency, seasoned with some high cultural theory.

Cultural Studies needs to engage with the horrific, the destructive, the violent-pornographic, the perverse, the vile and the prosaic in our present-day conjuncture, reassuming its key role of relentlessly uncovering the always hidden societal structures that generate oppression, suffering and death.

From this perspective, war becomes a borderline case, in which the celebration of human agency might not be the first and best choice. However important and truthful our celebration of agency, resistance and pleasure—and not to ignore the potential of these concepts to theorize and understand the social

—it is time to open Pandora’s box and attempt to (re)orient the Cultural (War) Studies toolbox towards an analysis of what limits our agency, what destroys our resistance, what perverts our pleasure, and what structures our bare existence. Cultural Studies needs to go to war again.

The Book

The main objective of the second edition of this book remains to make a modest contribution to the strengthening of Cultural War Studies. The book implicitly proposes a research agenda that would critically focus on the issues of ideology, representation, identities of Self and Enemy, power, pain and trauma, in relation to the oppressive forces of war.

This is not to say that Cultural War Studies should cut its connections with the theoretical and empirical practices of Cultural Studies; these will allow Cultural War Studies to build on an intellectual apparatus whose strengths (and weaknesses) have been proven.

The starting point for this book project was a panel session—entitled _Representing the New Cold War—_at the Fourth Annual Meeting of the Cultural Studies Association. The conference in which this session took place was held at the George Mason University in Arlington VA, U. S. A. , on April 19-22, 2006.

A series of panels at this and other conferences can be seen as the seeds of Cultural War Studies, which for too long has been restricted to the underground of Cultural Studies. The second edition was prepared a few years later, in the summer of 2014, not accidentally 100 years after the beginning of the First World War.

The structure of this edited volume mirrors the research agenda discussed in the present introduction. The first part of the book focuses on the diversity of media that generate meanings and definitions of past and contemporary wars. These chapters are not restricted to the more traditional analyses of media content, but utilize these media products to reflect on the contemporary cultural condition(s) in the U. S. A. and Europe.

Rebecca A. Adelman’s chapter looks at the representations of war generated by the memorialization of killed soldiers in Last Letters Home. Christina Lane’s analysis of the post 9-11 film Flightplan shows how this film facilitates the belief that the original (historical) trauma can be healed.

Metasebia Woldemariam and Kylo-Patrick R. Hart’s chapter takes us back to the Rwandan genocide, and its sometimes-problematic filmic representation in Hotel Rwanda. Karen J. Hall’s chapter acts as a bridge between the first and second parts of the book in analyzing the hard-core representations of war that circulate on the Internet, and the ways these images of torn bodies reproduce the dominant ideological model of war.

The second part of the book moves (at least partially) away from media representations and focuses on torture and incarceration. The practices in the name of “war against terror” in the 21st century have caused a number of shifts in the articulation of human rights, and their relationship with the notions of a just war and justifiable (state) violence.

The “use” of Guantánamo (and the disarticulation of its prisoners from the common forms of legal protection) has been defined—well within the framework of the ideological model of war—as regrettable but necessary and unavoidable in the war against terror. The “Ticking Time Bomb” argument has been articulated (as an alibi) to justify the increase in torture practices. Stephanie Athey’s chapter offers an important counter-narration to this and similar arguments that legitimize (state) torture, showing its complexity, and especially its omnipresence before and after 2001.

Usha Zacharias’ chapter looks at what occurred at Abu Ghraib, and the notions of imperial citizenship that made it possible. Although the second part of the book is quite short, it acts as an important interruption, halting the narrative flow of the book to foreground the extreme violence of torture.

The third and final part of the book consists of five chapters on issues related to memory and trauma. A series of (late 19th and) 20th century conflicts and wars are revisited to demonstrate the cultural durability of war and the interconnection of these wars with present-day discourses and practices through the dialectics of remembering, commemorating and forgetting.

Gordon Coonfield considers the flying of the flag after 9/11 as a ritual enactment by a traumatized nation. Vincent Stephens’s chapter analyzes A home at the end of the world and American pastoral to illustrate the workings of traumatized citizenship and national identity.

Marc Lafleur’s chapter revisits the A-bomb artifact, and the way that its history is re-narrated, transforming it from a destructive tool into a celebration of technology and nationhood. Tina Wasserman looks at the work of the Israeli journalist Amira Hass, in order to thematize the difficult relationship between the two traumata that haunt the Middle East: the Holocaust, and the Palestinian Occupation.

Finally, through the analysis of a 1937 film on the Dreyfus Affair, Nico Carpentier analyzes how a 19th century conflict becomes a grim portent of the horrors of the Second World War. In going back in time for more than a century, this chapter shows that analyses of cultural trauma should not remain confined to the present era, but require a historical dimension. This part of the book strongly reconnects with the first part in allowing for a reflection on the role of representational practices in the construction of memory and coping with trauma.

This reconnection signifies the dynamic process between the representations of traumatic events through a diversity of media, on the one hand, and on the other hand the representations of these events embedded in our memories, that render the (near) past present.

The best way to end a book on an important but not so pleasant topic is to revert to warm words. So I here wish to convey my gratitude to the external and internal reviewers for their (really) appreciated comments, to the staff of CSP for their assistance and good care, and to the authors of this book for combining a professional attitude with great insights, which made my work a fascinating learning experience. Thanks.

But this is also the place to express sadness, as one of our authors, Usha Zacharias, passed away on September 30, 2013. To commemorate her work, this second edition is dedicated to her. It is always difficult to summarize a life in a few words, but I believe we should remember especially her academic work on the cultural politics of gender, media and citizenship, but also her work as an activist in labor and feminist circles and her work as a film-maker. A more detailed In Memoriam was published by Carter and Hegde (2014) in Feminist Media Studies.

Notes

- Although the focus of this introduction (and the entire book) is on interstate war, a similarargument could be made for intrastate wars.

- Haraway’s (1991) discussion of these dichotomies has a specificfocus on the human/machine dichotomy.

- It can be argued that the different ideological models constructed by the different warring parties are inversed, but still similar in their core structure. Galtung (2009, 105), for instance, emphasizes the structural similarities of perceptions: “There are important symmetries in the perception, they are to some extent mirror images of each other, through imitation and projection. ” Given my cultural embeddedness in Belgium and Western Europe, the development of this model was unavoidably influenced by this specific cultural affinity, despite all attempts at cultural-intellectual empathy, curiosity, and understanding.

- The various names ascribed to this conflict are in themselves problematic. Calling it the Second Persian Gulf War (and the 1991 Gulf War the First Persian Gulf War) tends to exclude the ‘first’ Persian Gulf War, namely the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988). The absence of clear Western involvement seems to warrant its exclusion from the count. For this reason the more neutral‘2003 Iraqi War’ is preferred. Media are of course confronted with similar problems, and some made different choices, as Bodi (2004, 244-245) remarks:“Al Jazeera’s tag for the conflict was ‘War on Iraq’, in contrast to the BBC’s neutral ‘War in Iraq’ and Fox News’ jingoistic ‘Operation Iraqi Freedom’ which merely parroted the Pentagon’s name for the conflict. ” Moreover, the Iraqi War that started in 2003 is lasting longer than expected;for this reason also, the name ‘2003 Iraqi War’ is preferred to refer to the first period in this war, which started on March 19 2003 with the bombing of Baghdad, and ended when the US president George Bush declared the end of all major combat operations on May 1 2003, in his speech on the USS Abraham Lincoln. This signaled a new phase in the Iraqi war, which Seib (2004, 1) ironically calls the “post war war. ”

- Although contributing to the establishment of peace should be the ultimate and utopist horizon of Cultural War Studies, calling it Cultural Peace Studies would only assist in hiding the omnipresence of war and (neo) imperialism.

Works Cited

Ahmad, Aijaz. 2005. Contextualizing conflict. The U. S. “war on terrorism”. In War and the media. Reporting conflict 24/7. Edited by Daya Kishan Thussu and Des Freedman . London, Thousand Oaks CA, NewDelhi: Sage: 15-27.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1995. The gulf war did not take place. Bloomington IN: Indiana UniversityPress.

Bodi, Faisal. 2004. Al Jazeera’s war. In Tell me lies. Propaganda and distortion in the attack on Iraq. Edited by David Miller. London: Pluto Press, 243-250.

Bourke, Joanna. 1999. An intimate history of killing. Face-to-face killing in twentieth century warfare. London: Granta Books.

Buelens, Gert, Durrant Sam, and Eaglestone, Robert. 2014. Introduction. In The future of trauma theory. Contemporary literary and cultural criticism. Edited by Gert Buelens, Sam Durrant, and Robert Eaglestone. London: Routledge, 1-8.

Butler, Judith. 2009. Frames of war. When is life grievable? London: Verso.

Buttsworth, Sara, and Abbenhuis, Maartje M. (ed. ) 2010. Monsters in the Mirror: Representations of Nazism in Post-war Popular Culture. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Carpentier, Nico. 2005. Identity, contingency and rigidity. The (counter-) hegemonic constructions of the identity of the media professional, Journalism 6(2):199-219.

—. 2007. Fightingdiscourses. Discourse theory, war and representations of the 2003 Iraqi War. In Communicating war: Memory, media and military. Edited by Sarah Maltby. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Carter, Cynthia, and Hegde, Radha Sarma. 2014. In Memoriam—Usha Zacharias. Feminist MediaStudies 14(1): 3-4.

de Certeau, Michel. 1992. The writing of history. New York: Columbia UniversityPress.

Deuze, Mark. 2005. What is journalism? Professional identity and ideology of journalists reconsidered, Journalism, Theory Practice & Criticism6(4): 443-465.

Ellul, Jacques. 1973. Propaganda: The formation of men’s attitudes. New York: Vintage Books.

Erikson, Kai. 1976. Everything in its path. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Eyerman, Ron. 2001. Cultural trauma: Slavery and the formation of African American identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forty, Adrian, and Küchler, Susanne (Eds). 1999. The art of forgetting. Oxford: Berg.

Foster, Kevin. 1999. Fighting fictions. War, narrative and national identity. London: Pluto Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. History of sexuality. Part 1. An introduction. New York: Pantheon.

—. 1979. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Galtung, Johan. 2009. Theories of conflict. Definitions, dimensions, negations, formations. Oslo: Transcend.

Galtung, Johann, and Vincent, Richard C. 1992. Global glasnost: Toward a new world information and communication order? Cresskill NJ: Hampton Press.

Griffith, Robert. 2001. The cultural turn in Cold War Studies. Reviews in American History 29(1): 150-157.

Haggith, Toby, and Newman, Joanna (Eds). 2005. Holocaust and the moving image. Representations in film and television since 1933. London: Wallflower.

Hall, Stuart (Ed. ). 1997. Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. London, Thousand Oaks CA and New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Hall, Stuart, Critcher, Chas, Jefferson, Tony, Clarke, John, and Roberts, Brian. 1978. Policingthe crisis: Mugging, the state, and law and order. London: MacMillan.

Hallin, Daniel C. 1986. The “uncensored war”. The media and Vietnam.

Berkely, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1991. A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century. In Simians, cyborgs and women. The reinvention of nature. Edited by Donna Haraway. New York: Routledge, 149-181.

Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The generation of postmemory: Writing and visual culture after the holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press.

Howard, Michael. 2001. The invention of peace. Reflections on war and international order. London: Profile Books.

Jeffords, Susan. 2007. War. In Keywords for American Cultural Studies. Edited by Bruce Burgett and GlennHendler. New York: NYU Press.

Jowett, Garth. 1997. Toward a propaganda analysis of the Gulf War. In Desert Storm and the Mass Media. Edited by BradleyGreenberg and Walter Gantz. CresskillNJ: Hampton Press, 74-85.

Keen, Sam. 1986. Faces of the enemy. New York: Harper and Row.

Kellner, Douglas. 1992. The Persian Gulf TV War. Boulder CO, San Francisco CA, Oxford: Westview Press.

Knightley, Philip. 1982. The first casualtyofwar. London: Quartet. LaCapra, Dominick. 1999. Trauma. Absense, loss. Critical Enquiry 25(4):696-727.

Laclau, Ernesto, and Mouffe, Chantal. 1985. Hegemony and socialist strategy. Towards aradical democraticpolitics. London: Verso.

Laclau, Ernesto. 1990. New reflections on the revolution of our time. London: Verso.

—. 1996. Emancipations. London, Verso.

Lewis, Jeff. 2002. Cultural studies. The basics. London: Routledge.

McNair, Brian. 1998. The sociology of journalism. London, New York, Sydney, Auckland: Arnold.

Michael, George. 2002. Statement on Shoot thedog. DownloadedonMarch 15, 2004from http://george.michael.szm.sk/Lyrics/lyrstdog.html.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2005. Watching Babylon. The War in Iraq and global visualculture. New York: Routledge.

Papadakis, Yiannis. 2006. Toward an Anthropology of Ethnic Autism. In DividedCyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Edited by in Yiannis Papadakis, Nicos Peristianis and Gisela Welz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 66-83.

Reiter, Andrea. 2000. Narrating the holocaust. London: Continuum.

SantCassia, Paul. 2005. Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory and the Recoveryof Missing Persons in Cyprus. New York: Berghahn Books.

Schlesinger, Philip. 1987. Putting “reality” together. London and New York: Methuen.

Seib, Phillip (ed. ). 2004. Lessons from Iraq: The news media and the next war. The Lucius W. Nieman Symposium 2003. Milwaukee WI: MarquetteUniversity.

Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the pain of others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Stewart, Ian, Carruthers, Susan L. 1996. War, culture and the media. Representations of the military in 20th centuryBritain. Trowbridge, Wilts:Flicks Books.

Taithe, Bertrand, and Thornton, Tim. 1999. Propaganda: A misnomer of rhetoric and persuasion? In Propaganda. Political rhetoric and identity 1300-2000. Edited by Bertrand Taithe and Tim Thornton. PhoenixMill: Sutton Publishing, 1-24.

Taylor, Philip M. 1995. Munitions of the mind: A history of propaganda from the ancientworld to the presentera. Manchester: Manchester UniversityPress.

Torfing, Jakob. 1999. New theories of discourse. Laclau, MouffeandŽižek. Oxford: Blackwell.

Tuchman, Gaye. 1972. Objectivity as a strategicritual: An examination of newsmen’s notions of objectivity. American Journal of Sociology 77: 660-679.

Virilio, Paul. 1989. War and cinema: The logistics of perception. London: Verso.

—. 2002. Desert screen. War at the speedof light. London: Continuum. Zelizer, Barbie (ed.). 2001. Visual culture and the Holocaust. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 1989. The sublime object of ideology. London: Verso.

—. 2002. Welcome to the desert of the real. London and New York: Verso.

—. 2004. Iraq: The borrowed kettle. London and New York: Verso.