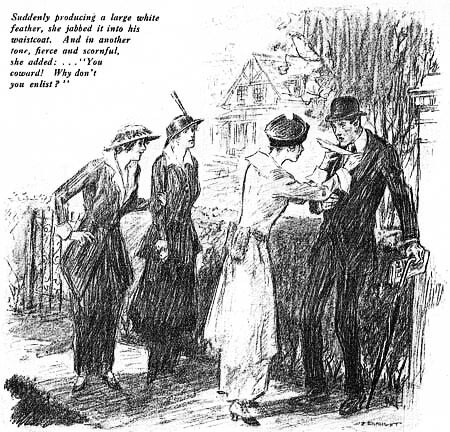

Women would place a white feather, a symbol of cowardice, on a man in civilian clothing to humiliate him for shirking military service. This symbol originated from the belief that a white tail feather was a sign of inferior breeding in a rooster bred for cockfighting. Showing the white feather meant the bird lacked the aggression necessary to succeed in the sport. The White Feather Campaign began in 1914, but continued long after conscription in 1916. Peter Hart notes that women were almost as effective as conscription in recruiting men for the war effort. Gullace writes:

Since being a soldier was the standard of masculinity, a white feather was intended to convey to its recipients the message that he was not a real man. Gullace notes that the white feather campaign has received “only passing attention from historians of the war.” Feminist scholars in Britain and America focused on the “much celebrated history of feminist pacifism,” and tended to dismiss the white feather campaign as misogynistic propaganda meant to “discredit women and hide the more significant achievements of feminist pacifists.” As there is abundant evidence of the prevalence of this ritual, Gullace attributes this exclusion to the shameful significance this practice acquired after the war. There was backlash against this practice because it was done indiscriminately: Since any man seen in public in civilian clothing was suspected of shirking his civic duty, veterans who had been honorably discharged were frequently targeted. Thus in the later stages of the war, the white feather campaign increasingly was seen as “an outrageous disruption of public order rather than as an even marginally legitimate means of coaxing or cajoling men to the colors.” As the cruel consequences of sending people to war became evident, the practice began to jeopardize women’s image as innocent, kind and caring. Since the historical record has established that many women enthusiastically participated in this practice, we may now ask why. Why did women want to take such an active role in sending their countrymen to war? During the period of voluntary recruiting, vigorous propaganda called on women to send their men to war, but this may not be the only reason women chose to bestow the feathers on men. Peter Hart speculates that in addition to satisfying their patriotic impulse to participate in the war effort, the white feather campaign gratified the women who participated because it gave them power over men, who usually ruled over them. This power derived from the fact that men feared the shame of the white feather presented by a woman more than they feared a gruesome death on a battlefield. This was true because these women had more power than they realized: They were a continuation of the long history dating back to ancient Sparta of women as important motivators of men to become war heroes. But there is something paradoxical about the assumption that military service implies strength & masculinity. Serving in the military means submission to authority and self-sacrifice. The soldier goes to war to forfeit his particular body for that of the larger body, the body politic, a body most often represented as feminine. In an effort to avoid being perceived as feminine, the soldier subordinates himself to a larger entity that is conceived as feminine. |