About the Author

Nicoletta Gullace is Associate Professor of History at the University of New Hampshire, where she teaches history and international affairs. Her research interests are in modern Britain, European cultural history, and women's history. |

Book by Nicoletta Gullace

For information on purchasing this book through Amazon at a special discount rate, click here.

In this extraordinary study of the complex relationship between war, gender, and citizenship in Great Britain during World War I, Nicoletta F. Gullace shows how the assault on civilian masculinity led directly to women's suffrage.

Through recruiting activities such as handing out white feathers to reputed "cowards" and offering petticoats to unenlisted "shirkers," female war enthusiasts drew national attention to the fact that manhood alone was an inadequate maker of civic responsibility. Proclaiming women's exemplary service to the nation, feminist organizations tapped into a public culture that celebrated military service while denigrating those who opposed the war. |

|

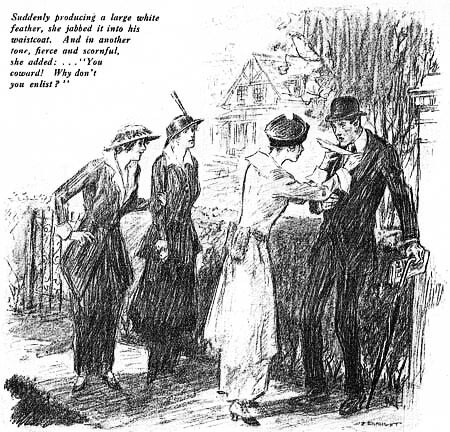

Suddenly producing a large white feather, she jabbed it into his waistcoat. And in another tone, fierce and scornful, she added: ..."You coward! Why don't you enlist?" Suddenly producing a large white feather, she jabbed it into his waistcoat. And in another tone, fierce and scornful, she added: ..."You coward! Why don't you enlist?"

Image from 'The White Feather: A Sketch of English Recruiting' by Arnold Bennett, Collier’s Weekly 1914

|

|

On August 30, 1914, Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald, an inveterate conscriptionist and disciple of Lord Roberts, deputized thirty women in Folkstone to hand out white feathers to men not in uniform. The purpose of this gesture was to shame "every young 'slacker' found loafing about the Leas" and to remind those "deaf or indifferent to their country's need" that "British soldiers are fighting and dying across the channel."

Fitzgerald's estimation of the power of these women was enormous. He warned the men of Folkstone that "there is a danger awaiting them far more terrible than anything they can meet in battle," for if they were found ‘‘idling and loafing to-morrow" they would be publicly humiliated by a lady with a white feather.

The idea of a paramilitary band of women known as "The Order of the White Feather" or "The White Feather Brigade" captured the imagination of numerous observers and even enjoyed a moment of semiofficial sanction at the beginning of the war.

According to the Chatham News, an "amusing, novel, and forceful method of obtaining recruits for Lord Kitchener's Army was demonstrated at Deal on Tuesday" when the town crier paraded the streets and "crying with the dignity of his ancient calling, gave forth the startling announcement: "Ladies wanted to present the young men of Deal and Walmer—the Order of the White Feather for shirking their duty in not coming forward to uphold the Union Jack of Old England! God save the King.'"

Numerous women responded to the cry and began to comb the city placing white feathers in the lapels and hat bands of men wearing civilian clothes. The practice was widely imitated by women all over the country and continued long after conscription was instated in 1916, creating one of the most persistent memories of the home front during the war.

"Women of Britain Say-'GO'!"

The white feather campaign originated within a system of voluntary recruiting that vociferously called on women to send their men to war. Until the institution of conscription in 1916, recruiting propaganda relied heavily on a patriotic appeal that welded masculinity to military service and branded the unenlisted civilian as a coward beneath contempt.

As early as August 1914, personal advertisements appearing in The Times accused unenlisted men of cowardice and effeminacy in the name of presumed female acquaintances. "It will not be very long before every woman in the country will be looking 'coward' at every man she sees at home," The Times forebodingly warned. For the writer "has talked with six women, varying in station from servant-maid to marchioness, all of whom have asked why so many young and active men are seen around who do not appear to be doing anything about going to war."

Recruiters, legally barred from resorting to conscription until the enactment of National Service in 1916, put much thought into the motivation of young men, appealing both to threatened masculinity and to sexual desire as means of persuasion. In this way, Henry Arthur Jones was using commonplace logic when he declared that "the English girl who will not know the man-lover, brother, or friend—that cannot show an overwhelming reason for not taking up arms-that girl will do her duty and will give good help to her country."

The incitement to such tactics was by no means unusual, especially during the first two years of the war. One recruiting leaflet addressed to "MOTHERS!" and "SWEETHEARTS" reminded mothers of Belgian atrocities and warned sweethearts that, "If you cannot persuade him to answer his Country's Call and protect you now Discharge him as unfit!"

A poster designed for the lord mayor of London (a copy of which appears to the right) put the same message even more bluntly. Addressing "The Young Women of London," the mayor asked: "Is your 'Best Boy' wearing Khaki? If not don't YOU THINK he should be? If he does not think that you and your country are worth fighting for—do you think he is worthy of you?

"Don't pity the girl who is alone—her young man is probably a soldier—fighting for her and her country—and for You. If your young man neglects his duty to his King and Country, the time may come when he will Neglect You. Think it over—then ask him to JOIN THE ARMY TO DAY!"

In this way, while "Women of Britain" were told to "Say Go!" something as private as female sexuality took on a military significance at the expense of all those unenlisted men who appeared reluctant to defend its sanctity. While this poster and others like it were criticized in Parliament and in the feminist press for their blatant manipulation of gender, the state had nevertheless assumed the guise of a woman for the purpose of recruiting.

Sexual Selection and Imperial Order

The inspiration for the use of the white feather, and its significance in the construction of masculine honor and feminine disdain, were borrowed from The Four Feathers, a popular imperial adventure by A. E. W. Mason first published in 1902. The white feather of cowardice referred to the white feather in a game bird's tail widely regarded as a mark of inferior breeding. In popular parlance to "mount" or "show" the white feather was to display signs of cowardice, since a properly bred fighting cock would demonstrate the aggression and tenacity valued in the ring.

The symbol of the white feather thus bound together issues of sexual selection, bravery, and cowardice—a confluence highlighted in the novel, which had gone into four editions by 1918. In the novel Harry Feversham, a young military officer who cannot stand the thought of battle, resigns his commission on learning that he is to be sent to the Sudan on active duty.

Suspecting the cowardly motives behind his resignation, three of Harry's comrades send him white feathers forcing him to confront the devastating truth of his own martial inadequacy. The emotional climax of the novel comes when Harry must offer an explanation of the incident to his fiancée Ethne.

As the narrator dramatically explains, "The dreadful thing for so many years dreadfully anticipated had at last befallen him. He was known for a coward. It was the girl who denied, as she still kneeled on the floor. 'I do not believe that it is true,' she said. 'You could not look me in the face so steadily were it true. Three little white feathers,' she said slowly and with a sob in her throat, 'three little white feathers and the world's at an end.'"

After returning her engagement ring, Ethne breaks a white ostrich feather from her ornamental fan and returns it to Feversham along with the three original feathers. As the narrator explains: "The thing which she had done was cruel no doubt, but she wished to put an end—a complete, irrevocable end. She was tortured with humiliation and pain. Their lips had touched—she recalled with horror."

This final act of humiliation at the hands of the woman he loves spurs Harry to redeem himself—a redemption possible only in the spilling of blood. On leaving Ethne, Harry embarks on a trek to the Sudan to save his former friends from rebellious Dervishes who have refused to submit to colonial rule. In Africa, his symbolic passage to manhood occurs when Harry sinks his untried dagger into the body of an Arab, infusing his sanguinary quest for personal courage with visceral phallic imagery.

"A brown clotted rust dulled the whole length of the blade, and often he had taken the knife from his breast and stared at it with incredulous eyes and clutched it close to him like a thing of comfort. He ran his fingers over the rough rust upon the blade, and the weapon spoke to him and bade him take heart."

As Harry caresses the dried blood of his victim—a testimony and proof of manhood encrusted on the very blade of his knife—the novel's juxtaposition of sex and empire begins to emerge, vividly highlighting a number of cultural assumptions that underlay the bestowal of the white feather of cowardice.

In the novel, imperialism and sexuality are intimately related since the masculine traits needed to satisfy the woman are the same as those required in the conquest of empire. After rescuing his comrades from the clutches of Dervishes, proving his willingness to kill and his indifference to danger and death, Harry's redemption is complete and he is able to return the feathers and reclaim his bride.

On Harry's heroic return, Ethne treasures his redeemed white feather "because it was no longer a symbol of cowardice but a symbol of cowardice atoned." The mock order of the white feather becomes instead the true badge of courage, as Harry's atonement allows for the rehabilitation of his name and his reintegration into the society of his friends, his family, and the woman he loves.

As both the symbol of Harry's humiliation and the instrument of his redemption, the white feather endows womanly scorn with rich creative possibilities. For wartime enthusiasts, the objective of giving a white feather was thus not only to shame a man, but to change him as well, and as numerous men later testified, it could be wielded with a certain amount of patriotic self-righteousness by those would-be Ethnes who regarded a slacker as an affront to the ideal of manhood itself.

A. M. Woodward perfectly summed up this attitude when she wrote to The Times to remind women that "there is a wider duty than making garments. Young men must be persuaded to think what this war really means. So I am commencing a little missionary work. Tomorrow I mean to give a leaflet to every man who is apparently a possible recruit. I shall watch for them on the tram, in the street, at cricket and tennis grounds, at the theater, at the restaurant; and I hope that the little single appeal 'from the women of England' will at least rouse their thought and will possibly help them to act."

The imperial/sexual assumptions evident in The Four Feathers pervaded both the language of patriotic femininity and the ideal of romantic love during the war. If courage was the key to both sexual selection and the conquest of empire, every woman's imperial/eugenic task was to love a soldier and scorn a coward. As the Girl's Own Paper solemnly explained, "Women will forgive almost anything in a man except cowardice and treason."

For "not only is this feeling instinctive, but it comes to her through long years of human evolution. With hearts full but tranquil souls, women can send forth their sons, their husbands, their sweethearts, their protectors, to danger or to death—to anything saving halting and dishonour. A great Admiral put it neatly when he said 'victory was won by the woman behind the man behind the gun."'

In the suggestion that both women and war demanded the same qualities out of a man, female sexuality became central to contemporary understanding of the forging of martial identity. "The soul's armour is never well set to the heart unless a woman's hand has braced it," the Mother's Union warned, "and it is only when she braces it loosely that the honour of manhood fails."

During the war, female journalists, music hall entertainers, and an array of patriotic publicists of both sexes popularized these sentiments by articulating women's military purpose in terms of their sexual and moral power over men. Indeed, if the act of bestowing a white feather required no words to be understood, it may have been because contemporary discourse about women's influence gave unmistakable meaning to a gesture that invested feminine discrimination with explicit military utility.

When the Baroness Orczy, author of The Scarlet Pimpernel, called for the "First Hundred Thousand" female recruiters to join her "Active Service League" in 1914, she made explicit the logic latent in such patriotic acts of feminine disdain. "Women and Girls of England—Your hour has come," the Baroness declared. "The great hour when to the question 'what can I do?' your country has at last given an answer.

"Women and girls of England," she says, "I want your men, your sweethearts, your brothers, your sons, your friends. Will you use your influence that they should respond one and all? Women and girls of England, you cannot shoulder a rifle, but you can actually serve her in the way she needs most. Give her the men whom she wants use all the influence you possess to urge him to serve his country."

The baroness posed the influencing of men as literally a form of "active service" for women, and offered a military style badge and a place on the League's "Roll of Honour" to any woman or girl who pledged to "persuade every man I know to offer his service, and never to be seen in public with any man who being in every way fit and free has refused to respond to his country's call." The baroness succeeded in enrolling 20,000 women and for her efforts received a letter of commendation from the king. Yet Orczy was merely one of a multitude of commentators and patriots who bade women to persuade their men to enlist and to scorn those who refused.

To Orczy, the withdrawing of the feminine body—in the refusal to be seen in public with a man out of uniform—worked in conjunction with moral coercion to isolate the man who refused to enlist. Her assumption seems to have been that what persuasion and female patriotism could not achieve, sexual desire and public shame could. If the presence of women were contingent on the wearing of a uniform, the purpose of the League was to assure that the signs of military and sexual prowess would be worn together or not at all.

At venues ranging from local music halls to carnivalesque recruiting rallies, the alleged contingency of love on war dominated the period of voluntary recruiting, turning military service itself into a sort of national aphrodisiac. In the most famous recruiting song of the war, women explained that:

"Now your country calls you

To play your part in war.

And no matter what befalls you

We shall love you all the more.

Oh, we don't want to lose you.

But we think you ought to go.

We shall want you and miss you.

But with all our might and main.

We shall cheer you, thank you, kiss you

When you come back again."

Female entertainers themselves frequently tried to recruit men from the audience in the highly patriotic atmosphere of the music hall. Major D. K. Patterson, an "Old Contemptible" home on leave in 1915, went to the Royal Hippodrome in Belfast where a comedienne sang "We Don't Want to Lose You" directly to him. The mirth of the company surprised the vocalist who, much to Major Patterson's satisfaction, burst into tears on being told that he was already in the army.

The longing to transform men into soldiers and the virtual identification of erotic masculinity and martial prowess was as evident in popular women's fiction as in bawdy music hall lyrics. In August 1917, for example, Women at Home magazine published a romantic story by M. McD. Bodkin, K.C., called "The White Feather." In the story, Molly Burton, "a bright, pretty, warm hearted little girl and as brave as another" accidentally gives a white feather to a recipient of the Victoria Cross.

Molly is intensely drawn to posters "urging young men to join their comrades in the trenches, to fight for England and liberty against the ravishers and murderers in Flanders." Shirkers and slackers awakened her utmost scorn. "If I were a man," she said, "I would go at first call. I would not have other men out fighting for me while I skulked at home amongst the women."

Molly is troubled by the presence in the neighborhood of "a splendid figure of a man" who was not at the Front. Molly could not bear the sight of "the handsome young lounger" for "here was indeed a slacker in excelcis for whom no excuse was possible to linger ingloriously at home while his compeers were facing the horror of war."

Molly's contempt grows daily as she sees the handsome coward "lazing around Brighton, while England, through the medium of many-coloured and illustrated posters, proclaimed that every man was needed at the Front." Finally, able to stand it no longer, she gives him a white feather snipped from her favorite hat.

The culmination of the story and the fruition of its sexual/military motif, comes when Molly is invited to a grand ball "for a military angel, Robert Courtney, most illustrious of Victoria Cross heroes who has been residing anonymously at Brighton for nearly a fortnight." Predictably, "the hero of the Victoria Cross was her slacker, still wearing the White Feather." The revelation of his bravery solves the puzzle of how Molly could have found herself "in danger of loving this self-confessed slacker", and culminates in the conflation of romantic and martial masculinity in the person of the hero.

As the narrator explains, Captain Courtney "waltz’s as he fought, superbly." In the final passage of the story he "caught her close in his arms, half resisting, wholly yielding, and kissed her on the lips. When she emerged panting and blushing from the close embrace without a word more spoken on either side, they were engaged." As the narrator reminds us, "Captain Courtney was no slacker in love or war!"

In the linking of patriotism and romantic imagination, the story offers some insight into why the categories of courage and cowardice, which became the foundation of women's romantic war literature, seemed to have inspired patriotic action in an assortment of women during the war.

In a context where waging war was regarded as the single most important civic task, the paradigm of courage and cowardice made it possible for women to envision national service in sexual terms. In turning women's romantic fantasies into supreme public duty, a variety of stories, songs, and patriotic appeals promised women a vicarious attachment to the front through the honor of the men they inspired, while elevating such amusements as the selection of beaux into tasks of national and imperial importance. |