| M. D. Faber's great book—in the tradition of Norman O. Brown and Ernest Becker—poses the question: "What would existence be like if we did not bind so desperately to the symbolic order?" Descartes said, "I think, therefore I am." Buddha countered: "I do not think, therefore I am." Faber proposes concentrative meditation as a technique to moderate our tie to objects, suggesting we focus on "direct, non-symbolic awareness of our body from the inside." We have just a few copies of this seminal work remaining in our warehouse (we will not be reprinting). Withdrawal of Human Projection is listed at $34.95 for the paperback and $39.95 for the hardbound. For a limited time, the sale price is $9.95. Click through to Amazon immediately to make sure you obtain your copy. Please scroll down to read the Table of Contents |

|

||||||

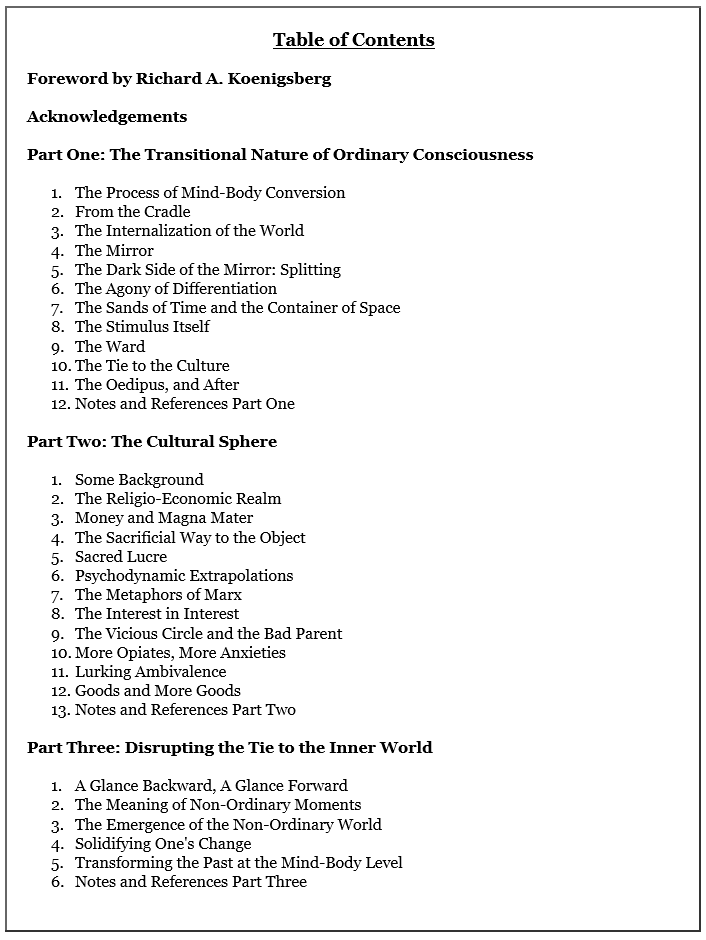

How we bind ourselves to the symbolic order. Cultural theory has been dominated by categories such as language and discourse. Like fish in water, we are so profoundly immersed within culture that we are barely reflect upon it—as something separate from our selves. In The Withdrawal of Human Projection: Separating from the Symbolic Order, M. D. Faber analyzes the psychological roots of attachment: why we bind ourselves so desperately to the symbolic order. We attach to society as a response to separation and separation anxiety. As we move away from our parents and family, we simultaneously link our identities to symbolic objects in culture. Each step toward autonomy, Faber says, holds the threat of loss, triggering an "endless search for replacement—for someone or something to fill the gap." Ordinary Consciousness "Ordinary consciousness" is our normal way of being in the world. As we struggle to separate and individuate, we simultaneously begin a ceaseless quest to unite with objects. We achieve separation by connecting to "transitional objects." Ordinary consciousness represents a perceptual condition in which we strive to "maintain our tie to the inner world by discovering substitute objects in the 'reality' of our cultural realm." Academic focus on culture is matched by its preoccupation with concepts like domination and oppression. Society is understood as both the ground of being—and the source of suffering. Faber claims that the experience of oppression stems from domination by the "objects within," whose persistent, implacable influence "stands squarely behind those forms of domination that characterize the social world." Within academic discourse, there is no place to go. One ideology struggles against another. One discourse is pitted in opposition to an alternative discourse. Given the inability or refusal to imagine existence apart from the symbolic order—there is no escape. Concentrative Meditation Faber proposes "concentrative meditation" as a technique to moderate the tie to objects. Withdrawal of human projection means "breaking" from our fetishistic attachment to society and symbol systems; moderating our tendency to project existence into culture; emptying the self of its objects. Faber suggests that we focus on "direct, non-symbolic awareness of one's body from the inside." Indeed, we have witnessed a revolution of the body—manifest in practices such as running, body-building and dancing. As grand narratives died, the center fell apart: human beings turned to the body as a new center of being. Embodiment became a hot topic. But much writing revolved around "discourses of the body" rather than the body itself. Descartes contra Buddha Descartes said, "I think, therefore I am." Buddha countered: "I do not think, therefore I am." In the academic world, French theorists won the argument. Yet even if we do not meditate—we know that we exist when we are not thinking. We possess feelings and fantasies, bodily sensations and erotic excitements, aches and pains—that exist below the level of language and discourse. Faber's Withdrawal of Human Projection proposes that we interrogate the nature of our relationship to the symbolic order rather than take it for granted. Why do we so vehemently assert that language and discourse constitute the ground of being? Faber also suggests that we consider pathological dimensions of our relationship to society. Culture may constitute reality, but at the same time our need to bind ourselves so profoundly to symbolic objects may reflect a flight from reality. To achieve a sense of stability and power, we connect with society and embrace the symbolic order. We assume "we are that." Simultaneously, we feel dominated and oppressed by the objects to which we have turned for salvation. What would existence be like if we did not bind so desperately to the symbolic order? In The Withdrawal of Human Projection, M. D. Faber asks us to imagine such a path.

|

||||||