|

|

| The Islamic martyr gives his life and blood for Allah. Soldiers of the First World War gave their lives and blood for entities called “Russia,” “Germany,” “France” “Romania,” “Italy,” “Turkey”—and “the British Empire.” In our hearts, the dream remains the same. | |

|

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George observed that during the First World War every nation was “profligate of its manpower and conducted the war as if there were no limit to the number of men fit to be thrown into the furnace to feed the flames of war.” The war, he said, was a perpetual, driving force that “shoved warm human hearts and bodies by the millions into the furnace.”

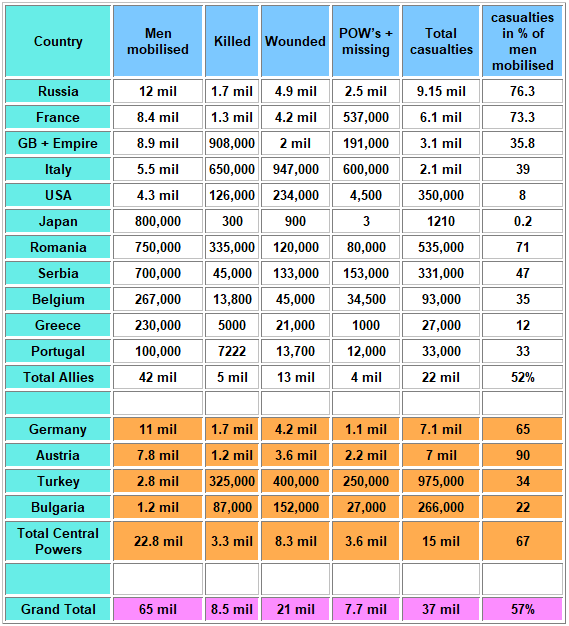

Many observers, however, thought the war was a good thing. P. H. Pearse—founder of the Irish Revolutionary movement—was thrilled by the carnage of the First World War: The last sixteen months have been the most glorious in the history of Europe. Heroism has come back to the earth. It is good for the world to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefield. Such august homage was never before offered to God as this—the homage of millions of lives given gladly for love of country. Pearse believed the war was good because it allowed the world to be “warmed with the red wine of the battlefield.” The death and mutilation of soldiers constituted an offering to God—"august homage”—the homage of millions of lives “given gladly for love of country.” In a similar vein, French nationalist Maurice Barrès said this about his nation's soldiers who were dying on a daily basis during the First World War: Oh you young men whose value is so much greater than ours! They love life, but even were they dead, France will be rebuilt from their souls which are like living stones. The sublime sun of youth sinks into the sea and becomes the dawn which will hereafter rise again. The death of a young man is sublime because it becomes the “dawn which will hereafter rise again.” Dead French soldiers regenerate the French nation. The First World War produced monumental destruction and massive numbers of casualties in the name of glorifying nations. Each nation proved its metal by sending young men to be slaughtered. The “greatest” nations were those that sent the largest number of men into the fray. However, many nations—not only great ones—wanted to be included. This is why we call it a “World War.” Nobody wanted to be left out (it's a family affair). A young village merchant speaking to a European sociologist in the 1980s provided a rationale for the religious violence occurring in the Middle-East: “The blood shed by the Iranian martyrs Is like the water of an irrigational canal which gives life to the crops. From it the religion will grow.” The dynamic of Islamic martyrdom expressed in this passage—that bloodshed is like water giving life to crops—is identical to the sentiment that P. H. Pearse expressed: that It is “good for the world to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefield.” Only the object of worship differs. The Iranian martyr gives his life and blood for Allah. Soldiers of the First World War gave their lives and blood for entities called “Russia,” “Germany,” “France” “Romania,” “Italy,” “Turkey”—and “the British Empire.” The difference between the soldiers of the First World War and Islamic suicide bombers lies in the quantity of the martyrs—and the degree to which people in the respective cultures are aware or conscious of the meaning of societal violence. Middle-Eastern radicals are aware that they undertake acts of violence in order to glorify Allah. People in the West, dominated by the fantasy or delusion that behavior arises out of “rational” considerations, often imagine that warfare is waged for “real” (e.g., economic) reasons. What's more, people in the West are so close to the objects they worship—gods called countries—that they cannot conceive that they produce vast forms of carnage in the name of glorifying these gods. The most “rational” of civilizations—most scientifically advanced and technologically sophisticated—is also the most unconscious. White, Matthew — First World War Casualties Source: Historical Atlas of the Twentieth Century.

|