The Human Body and the Body Politic, Chapter IV:

Overwhelmed by the Sovereign

Nazism was an extreme form of nationalism insisting upon absolute identification between self and country. Everything that followed—the history of Nazi Germany—was based on this equation of self with nation—of one’s own body with the German body politic. Nazism was based on submission to the omnipotent object, one’s nation. In its most extreme manifestation, submission to the nation took the form of dying for one’s country. Jews too enacted this fantasy of sacrificial submission: dying for Germany. Jews in the death camps replicated the sacrificial death of the German soldier. According to Nazism, everyone was required to sacrifice their lives for Germany. No one was exempt. Jews were not allowed to perform sacrifice through military duty. At the same time, they were not permitted to escape the sacrificial obligation. Death in the gas chambers constituted an alternative method of dying for Germany. In Nazi ideology, everyone was required to identify absolutely with the German nation. Therefore, the greatest sin or crime was separateness—separation from the nation. The Jew symbolized the idea or sin or crime of separation. Hitler understood Jews as a people who did not wish to bind their lives to a nation-state. Killing Jews represented the struggle to kill or kill off this idea of separateness or separation. Although Hitler advocated and embraced identification with the nation—claiming that devotion to Germany is a glorious, fulfilling experience, he also was burdened and oppressed by this identification, which drained his body and life. Thus, the recurring image of the “parasite,” which symbolized the omnipotent object in its negative, oppressive form—the nation as an object draining the life of the self. The Jew symbolized Germany: the oppressive, parasitical form of the dream of immortality. Jews represented submission to the omnipotent object in its negative guise: the destructive experience of identification with an omnipotent object. The Jew was Hitler’s experience of submission and sacrifice as painful; as well as his recognition that his project was in vain. It is futile to remain bound to the body politic; there is no such thing as bodies that do not die; the quest for immortality is a delusion. Having recognized the futility of his quest—the pain of submission to the omnipotent object—Hitler experienced the desire to separate from Germany (the fantasy of immortality). It is at this very moment (when he experienced a desire to separate from the fantasy of eternal union with Germany) that Hitler fell into a rage: “That no one can, no one must say to me: Germany must live.” What must “live” when Germany must live—is the fantasy of immortality; eternal union with the object. Hitler identifies Jews as the principle of separateness or separation: that which compels one to abandon the dream of immortality. Hitler cannot bear this experience. He cannot tolerate separation from the object, even though he knows deep down that attachment to Germany is the source of his suffering. What must be killed or killed off is the idea that attachment is painful and the source of suffering. What must be killed or killed off is one’s desire to separate from the object in order to liberate oneself from it. The Jew symbolizes Hitler’s desire to separate from the object that was draining him of his concrete existence. But he cannot bear to know this. The Jew contains Hitler’s desire for separation. Hitler needs to kill the Jew in order to kill his knowledge that sacrifice is in vain. Hitler proves the futility of dying for a country by producing the Holocaust. He acts out the knowledge that he has repressed. He provides a demonstration: it is not sweet and beautiful to die for a country; it is ugly and useless. His enactment functioned to demonstrate the ugliness and futility of dying for a country. The metaphors contained within Hitler’s writings and speeches reveals the meaning of Nazi ideology. Hitler’s ideology was the vehicle that allowed him to share his fantasies with the German people—to persuade them to embrace and act upon it. Hitler plugged his fantasies and desires into the ideology of nationalism. This ideology was the source of the history he created. History is created based on shared fantasies projected into the world, which are the basis of politics and constitute a certain form of reality. The history of the human race—with its recurring episodes of societally generated violence—consists of fantasies acted out to become reality. Fundamentally, it’s all nonsense. However, nonsensical though it may be, it’s also the basis of the historical process: dying and killing to prove the truth of ideologies conceived as absolutes. Each society puts forward an idea—a container for the fantasy of omnipotence. This idea, however, is contradicted by other ideas put forward as absolutes—believed to be indestructible and omnipotent. Wars are fought to prove the omnipotence of one’s own society’s idea. Ideologies die, and then other ones replace them. At a particular moment in time, the ideology that one’s society puts forth seems to be absolutely true—worth dying and killing for. Hitler represented the climax of this idea of dying and killing for an ideology conceived as absolute (until some society or group ignites an atom bomb in the name of its ideology). Hitler brought to fruition the fantasy of nationalism: countries as absolute entities that justify anything and everything. Group violence is precisely the opposite of “primitive aggression.” The most virulent forms of dying and killing that have occurred in the past two centuries are those undertaken in the name of some sacred ideal; an ideology conceived as an absolute. Things never worked out. Historians document each episode of mass-murder as if something new is occurring. It’s the same old, same old. People are thrilled that society goes on as usual, even as they condemn the violence. What is thrilling is that people still believe in some ideal. Therefore, the dying and killing can continue. Dying and killing represents a method of validation: proof of the pudding. Surely human beings are not dying for nothing. It is inconceivable that the history of human beings represents a form of psychosis. But it does. It is the normal psychosis of everyday life: the psychosis of history. Nobody wants to be left out. As long as the dying and killing continues to occur, there will be no end to history. Everyone colludes to keep the machinery going. Fantasies are projected into ideas or ideologies—belief systems—that are acted out and generate political reality. And the hits just keep on coming. When I speak of awakening from the nightmare of history, I’m suggesting that it is possible to see or perceive the unconscious fantasies that generate the historical process. Hitler revealed the essence of the fantasy that generated 20th Century history. It revolved around nations or societies as bodies politic—with which individuals fuse their own bodies (the image in the frontispiece of Hobbes Leviathan). Nations possess enemies that must be destroyed. An enemy represents that which contradicts the absolute idea that holds the body politic together. To awaken from the nightmare of history means contemplating the possibility that society or the body politic is an illusion; that history can end. Attachment to omnipotent bodies politic will not assure one’s immortality. In spite of all the sound and fury, one is going to die. At this moment—when one suggests that it is possible abandon the illusion of society—many people (like Emily Litella) say “never mind.” Better that the killing and dying continue—to maintain the illusion: History will never end. |

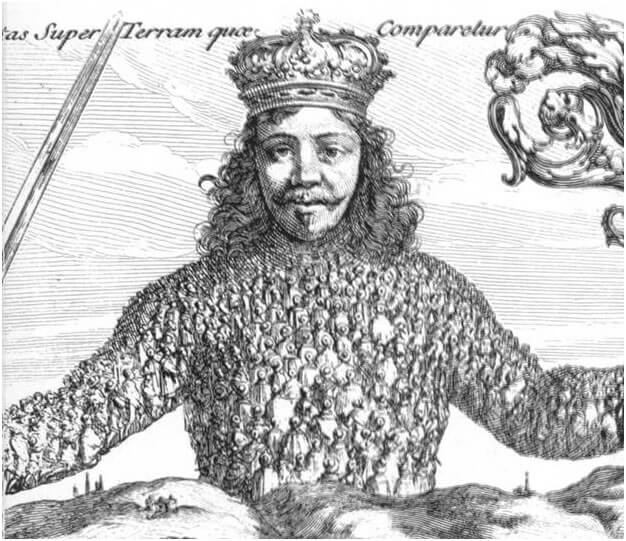

The famous frontispiece to Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan depicts the head and torso of a long-haired, mustachioed man. Upon close scrutiny, it becomes evident that the man’s torso and arms are composed of tiny individual persons, crowded closely together and each looking toward the head of the composite Leviathan.

The famous frontispiece to Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan depicts the head and torso of a long-haired, mustachioed man. Upon close scrutiny, it becomes evident that the man’s torso and arms are composed of tiny individual persons, crowded closely together and each looking toward the head of the composite Leviathan.