Who Won the Cold War?

|

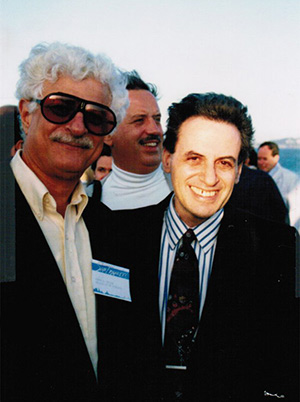

The photo below shows Dr. Vamik Volkan with Mikhail Gorbachev. Reading the LSS Newsletter, you’ll discover that you’ll find evidence that Volkan’s relationship with Gorbachev—and the field of political psychology—played a role in the fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989). The narrative of this event, of course, was that it marked America’s victory in the Cold War; the triumph of freedom over tyranny.

Nearly thirty years later—astonishingly—it begins to appear that the United States did not win the Cold War after all! It is extraordinary to see the American political leadership embracing a tyrannical political leader. Think of it: a forty-year struggle to defend freedom and democracy in opposition to dictatorship—risking a “nuclear Holocaust”—and now it seems that this project was delusory. In a paper by Howard F. Stein (1986), he suggests that the Soviet Union personified America’s “negative identity.” What was virulently repudiated was actually a part of the self. The Russian enemy embodied a “forbidden wish.” While Americans prized “freedom,” the Soviets were perceived as “menacingly and unremittingly trying to take freedom away.” Yet, Stein says, the perception of danger represented our own hostility toward freedom—attraction to authoritarianism—and desire for an authoritarian state. The United States maintained its precious value of freedom—by projecting the opposite of freedom onto Russia, who helped us to “manage our ambivalence.” The Soviet threat masked our disavowed desire. What we seem to witness now is the return of the repressed. What we once sought to keep at a great distance from the self—as far away as possible—now invades the boundaries of the United States. The enemy has become us. Best regards,Richard Koenigsberg, PhD Director, Library of Social Science |

|

||||||

| My introduction to this field occurred in July 1988 when I was invited to participated in a Panel at a meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology—with Vamik Volkan as co-presenter. Dr. Volkan works with diplomats and political leaders around the world to resolve international crises—and has been nominated four times for the Nobel Peace Prize. | ||||||

|

||||||

My research and writing falls under the rubric of Political Psychology, a discipline that began to take shape with the founding of the International Society of Political Psychology (in 1978). My introduction to this discipline occurred when I was invited to participate in a Panel at a meeting of the ISPP in July 1988, which Included Dr. Vamik Volkan as a co-presenter. Subsequent to the meeting, I began to learn more about the field of political psychology and the achievements of Dr. Volkan. An article appeared in Newsweek Magazine on August 28, 1989, “Why we all love to hate: Political psychologists bring hostile national groups together to explore the need for enemies.” Summarizing the work of several researchers, the article stated that having enemies “fulfills an important human need.” Volkan is quoted: “A psychological process goes on in international relations, and at the bottom of it lies this need to have enemies in our lives. We are trying to understand it.” He had been participating in a series of meetings dubbed “Track Two Diplomacy,” a kind of international group therapy whose purpose was to “establish ‘networking’ contacts between hostile groups.” Volkan was involved in a series of seminars between Egyptians and Israelis, and between the US and Soviets. According to the Newsweek article, there were signs that some of the ideas generated by these seminars were “registering in high places.” When Anwar Sadat asserted in a 1977 speech to the Israeli Knesset that the problems between the two nations were “70 percent psychological,” it sounded as if he had been tuning in to some of the meetings (a drafter of the Knesset speech had been a Track Two participant). When, Gelman wrote, “more astonishingly,” Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in a Kremlin speech welcoming Ronald Reagan hailed the overthrow of “habitual stereotypes stemming from enemy images,” political psychologists felt certain their dialogues were “paying off bigger than they dared hope.” The whole idea that enmity is a psychological concept, had “worked its way in important ways into Gorbachev’s speeches.” Volkan’s work grows out of the tradition of “conflict resolution,” which begins with the assumption that two opposing sides have different motives or interests, and that by engaging in dialogues or deliberation—the two sides can reach a conclusion or establish a settlement—that balances the interests of both parties. The conflict resolution tradition, in turn, is based on “rational choice theory,” which assumes that individuals have consistent preferences and goals, and that they are motivated to act in ways that maximize their “self-interest.” Rational choice involves choosing the course of action that “maximizes one’s expected utility.” My work is not designed to settle specific political conflicts. Rather, my objective is to identify the fundamental mechanisms that are source of collective forms of political violence. What’s more, based on research since my presentation in 1988, I have found that:

Based on these findings, the only “hope” to ameliorate political conflict and violence lies in understand how things work: revealing the central dynamics that are the source of collective forms of violence. This is why I often speak of awakening from the nightmare of history. It is a question of become conscious of the collective dream in which we are immersed. |