Chapter IV: The Sacrificial Theory of Warfare

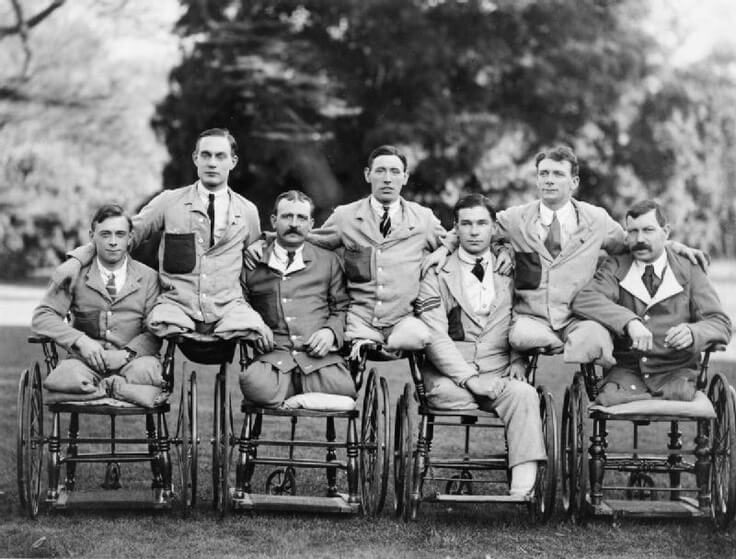

Sacrifice in warfare is a “gift” to one’s nation. The “supreme sacrifice” is one’s entire body. However, among the nine-million who did not die in the First World War were those who gifted a body part. In Dismembering the Male, Joanna Bourke (1996) observed that public rhetoric in Great Britain during and after the First World War judged soldier’s mutilations to be “badges of their courage,” the hallmark of their glorious service, “proof of patriotism.” The disabled soldier was not less but “more of a man.” A writer in The Times (1920) stated, “Next to the loss of life, the sacrifice of a limb is the greatest sacrifice a man can make for his country.” Richard A. Koenigsberg |

|