Chapter XIII: The Psychological Interpretation of Culture and History

|

|||

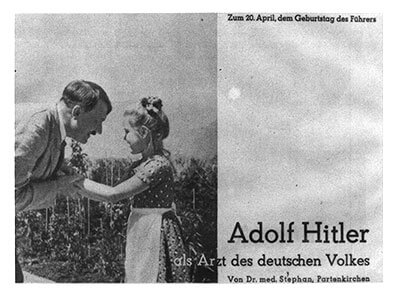

From the earliest days of National Socialism, Hitler and other Nazis were haunted by the specter of a disease within the body politic that could lead to the death and disappearance of the German nation. Subsequent to the First World War, Hitler felt that the German people were suffering—and believed that the suffering of his people was the result of the fact that they had acquired a disease. The first task of a German politician, therefore, was to diagnosis the nation’s disease—disclose its cause. In Mein Kampf (1923), Hitler stated that the efforts of ordinary German politician—who were "tinkering around on the national body"—was condemned to sterility because the best of them "saw at most the forms of our general disease and tried to combat them, but blindly ignored the virus." Ordinary politicians were aware that Germany was ill, but did not dig deeply enough. They were unable or unwilling to comprehend the causes of Germany's disease. Hitler, by contrast, would stake his claim to leadership based on his capacity to diagnosis and cure Germany's illness. He believed that people would follow a political leader who "profoundly recognizes the distress of his people," works to attain the "ultimate clarity regarding the nature of the disease," and then "seriously tries to cure it." Hitler aspired to become "Doctor of the German people." Reflecting on Germany's disease in Mein Kampf, Hitler asserted that every distress has "some root or other." It was not enough for the Government to issue emergency regulations amounting to "doctoring around on the circumference of the distress” and trying “from time to time to lance the cancerous ulcer." It was necessary, rather, to penetrate ”to the seat of the inflammation—the cause." Whether the irritating cause was discovered or removed today or tomorrow was unimportant, the essential thing was to realize that "unless it is removed no cure is possible." Hitler identified the Jew as the source and cause of Germany's disease. He viewed Jews as pathogenic microorganisms whose continuing presence within the nation would lead to its demise. It was necessary, therefore—to cure Germany's disease—to eliminate the Jew from within the body politic. The Nazi movement was conceived as a struggle of life against death; between the healthy German organism, and the viral Jewish element. In order to combat the German disease, Hitler believed it was necessary to mobilize the will of the German people—to fight the disease. Hitler challenged his people: Do you have the insight to perceive the cause of Germany’s disease? Do you have the courage to rise up and take action against it? Germans would have to “enter the fight against death”—and rise up against the fate that had been planned for them. Or else the nation would sink, and the German people—"through their despicable cowardice” would sink with it. Taking action meant doing whatever was necessary to save the life of the nation. A momentous struggle would ensue to determine "which is stronger: the spirit of international Jewry or the will of Germany." From the beginning of his career, Hitler framed his ideology in terms of this "either-or" conception. "The future of Germany," he declared, means "the annihilation of Marxism." Either the "racial tuberculosis" would thrive and Germany would die out; or it would be "cut out of the Volk body," and Germany would thrive. The Final Solution involved cutting out the racial tuberculosis—in order to save the life of the German organism. |