Thirteenth chapter of Dynamics of Mass Murder

|

||||

| The best account of Hitler as a soldier, 1914-1918, appears in Adolf Hitler: The Making of a Fuhrer, an online publication by Walter Smoter Frank. A major source of the material below is Frank’s Chapter 9: A Born Soldier. | ||||

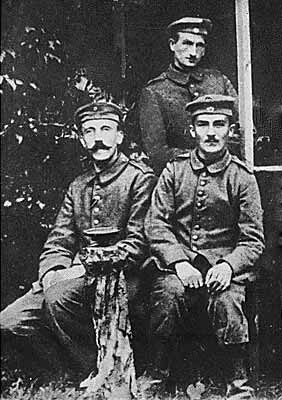

Hitler fought for Germany throughout the First World War, 1914-1918. This is not the place to provide a history of Hitler the soldier. However, we need a sense of what he went through—the dreadful experience of a German soldier during the First World War. What was it, precisely, that Hitler refused to complain about? Hitler was 25 years old in August 1914 when Austria-Hungary and the German Empire entered the First World War. Because of his Austrian citizenship, Hitler had to request permission to serve in the Bavarian Army. Permission was granted, and Hitler was summoned to report to the 16th Infantry Regiment on August 16, 1914. Hitler served in France and Belgium in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment. He was an infantryman in the 1st Company during the First Battle of Ypres (October 1914), which is remembered in Germany as the Kindermord bei Ypern (Massacre of the Innocents) because approximately 40,000 men (between a third and a half) of nine newly enlisted infantry divisions became casualties in 20 days. Hitler's regiment entered the battle with 3,600 men and at its end mustered 611. On October 5, 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, Hitler was struck in the thigh by a fragment of a grenade which exploded at the door to the dugout where he and several fellow runners had taken cover. The wound was serious, but not life-threatening. Hitler was sent to a military hospital back in the Reich, and was returned to his unit as soon as he recovered. On October 15, 1918, Hitler was wounded in the Ypres Salient in Belgium—blinded by a British mustard gas attack. He was evacuated to a German military hospital at Pasewalk and was being treated there—when on November 10, 1918 he learned that Germany had surrendered. Frank reports that casualties in Hitler's regiment, severe from the start of the war, mounted steadily. The chances that a 1914 volunteer of the List Regiment would be killed or maimed was almost guaranteed. Because of replacements, Hitler's Regiment, which consisted of 3,600 men in 1914, suffered 3,754 killed before the war ended. Mass burials of whole and partial corpses became commonplace. Gary Mead witnessed a mass burial in which corpses sprinkled with lime were placed into a grave in a layer of thirty. Straw was placed over the dead and another layer of bodies was placed over the first until the grave held over 100 bodies. Thousands of other recruits lost limbs, parts of torsos, sight, hearing and also their minds. "Thus, it went on year after year," Hitler would later write, "but the romance of battle had been replaced by horror." Hitler had experienced the nightmare of the First World War. Yet, he did not become an anti-war activist. Indeed, he refused to complain about what he had gone through—or to blame Germany. What’s more, in spite of everything, through the rest of his life he embraced war. This contradiction lies at the heart of this inquiry: How is it that a man has experienced the awfulness of warfare first hand, yet does not condemn war? How is it possible that a man has witnessed the suffering and death of hundreds of his comrades, yet refuses to complain about this? |