|

||||||

|

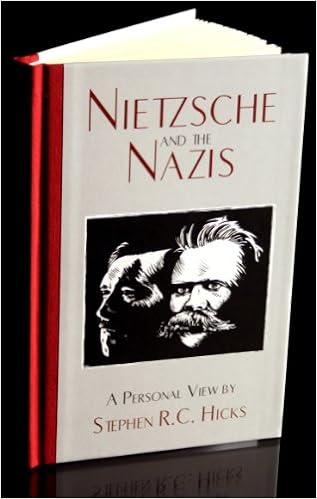

The quotes below have been selected from Appendix 4, Nietzsche and the Nazis. Click here to download the complete list of quotations as a PDF. |

||||||

Franz Felix Kuhn (1812-1881), philologist and folklorist: “Must culture build its cathedrals upon hills of corpses, seas of tears, and the death rattle of the vanquished? Yes, it must.” Otto von Gottberg (1831-1913), writing in the newspaper Jungdeutschland-Post in January 1913: “War is the most august and sacred of human activities. Let us laugh with all our lungs at the old women in trousers who are afraid of war, and therefore complain that it is cruel and hideous. No! War is beautiful.” Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900): “I welcome all signs that a more manly, a warlike, age is about to begin, an age which, above all, will give honor to valor once again. For this age, shall prepare the way for one yet higher, and it shall gather the strength which this higher age will need one day—this age which is to carry heroism into the pursuit of knowledge and wage wars for the sake of thoughts and their consequences.” Nietzsche: “War essential. It is vain rhapsodizing and sentimentality to continue to expect much (even more, to expect a very great deal) from mankind, once it has learned not to wage war. For the time being, we know of no other means to imbue exhausted peoples. as strongly and surely as every great war does, with that raw energy of the battleground, that deep impersonal hatred, that murderous cold-bloodedness with a good conscience, that communal, organized ardor in destroying the enemy, that proud indifference to great losses, to one’s own existence and to that of one’s friends, that muted, earthquakelike convulsion of the soul.” Friedrich von Bernhardi (1849-1930), general, military historian, author of Germany and the Next War (1911): “While the French people in savage revolt against spiritual and secular despotism had broken their chains and proclaimed their rights, another quite different revolution was working in Prussia—the revolution of duty. The assertion of the rights of the individual leads ultimately to individual irresponsibility and to a repudiation of the State. Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855-1927), English-born German author and propagandist: “He who does not believe in the Divine Mission of Germany had better go hang himself, and rather today than tomorrow.” Otto Richard Tannenberg, author of Greater Germany, the Work of the Twentieth Century, writing in 1911: “War must leave nothing to the vanquished but their eyes to weep with.” Max Scheler (1874-1928), philosopher at the universities of Jena, Munich, and Cologne, writing on the German ideology: “It would set faith against skepticism, metaphysics against science, the organic whole against atomism, life against mechanism, heroism against calculation, true community against commercialized society, a hierarchically ordered people against the mass leveled down by egalitarianism.” Thomas Mann (1875-1955), novelist and essayist, echoing the desire to eliminate the old world of bourgeois hypocrisy, thought the First World War would end that “horrible world, which now no longer is, or no longer will be, after the great storm passed by. Did it not crawl with spiritual vermin as with worms?” Writing during the war of his pre-war days: “We knew it, this world of peace. We suffered from this horrible world more acutely than anyone else. It stank of the ferments of decomposition. The artist was so sick of this world that he praised God for this purge and this tremendous hope.” Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), author of Storm of Steel. In war, “the true human being makes up in a drunken orgy for everything that he has been neglecting. Then his passions, too long damned up by society and its laws, become once more dominant and holy and the ultimate reason.” “This war is not ended, but the chord that heralds new power. It is the anvil on which the world will be hammered into new boundaries and new communities. New forms will be filled with blood, and might will be hammered into them with a hard fist. War is a great school, and the new man will be of our cut.” Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), author of The Decline of the West: “We must go right through to the end in our misfortune; we need a chastisement compared to which the four years of war are nothing. A dictatorship, resembling that of Napoleon, will be regarded universally as a salvation. But then blood must flow, the more the better.” Otto Braun, age 19, volunteer who died in World War I, in a letter to his parents: “My inmost yearning, my purest, though most secret flame, my deepest faith and my highest hope—they are still the same as ever, and they all bear one name: the State. One day to build the state like a temple, rising up pure and strong, resting in its own weight, severe and sublime, but also serene like the gods and with bright halls glistening in the dancing brilliance of the sun—this, at bottom, is the end and goal of my aspirations.” G. W. F. Hegel (1770-1831) on World-historical individuals, those whom the march of history has selected to advance its ends: “A World-historical individual is not so unwise as to indulge a variety of wishes to divide his regards. He is devoted to the One Aim, regardless of all else. It is even possible that such men may treat other great, even sacred interests, inconsiderately; conduct which is indeed obnoxious to moral reprehension. But so mighty a form must trample down many an innocent flower—crush to pieces many an object in its path.” Commentators on Germany in the 19th and early 20th centuries. American historian William Manchester on 19th century Germany,: “the poetic genius of the youth of Germany was saturated with militaristic ideals, and death in battle was prized as a sacred duty on behalf of Fatherland, home, and family.” Ernst Gläser (1902-1963), German novelist expressing the prevailing spirit of 1914,: “At last life had regained an ideal significance. The great virtues of humanity—fidelity, patriotism, readiness to die for an ideal were triumphing over the trading and shopkeeping spirit. This was the providential lightning flash that would clear the air [and make way for] a new world directed by a race of noble souls who would root out all signs of degeneracy and lead humanity back to the deserted peaks of the eternal ideals. The war would cleanse mankind from all its impurities.” |