|

|||

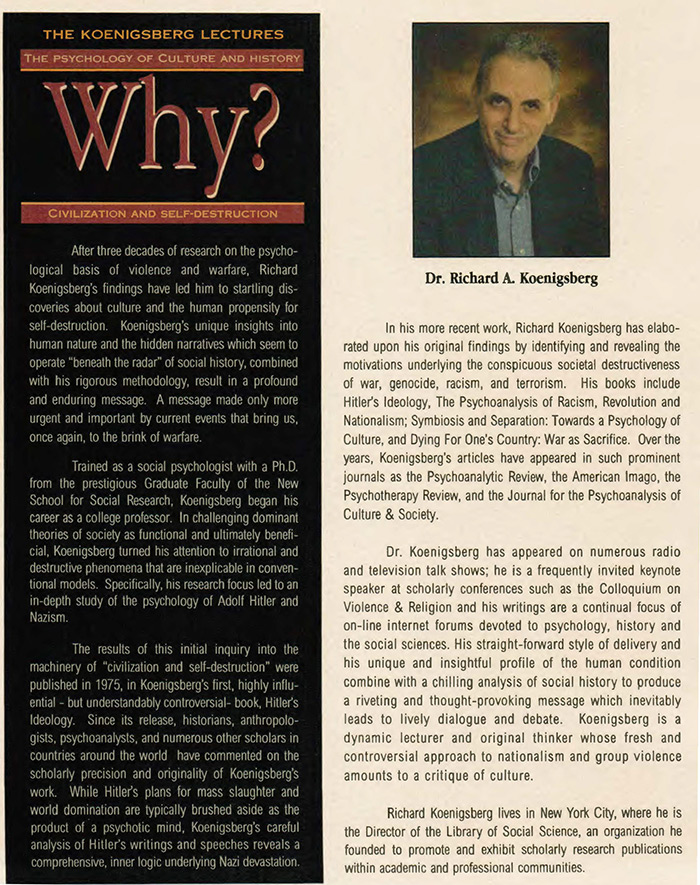

Based on the topics in the promotion piece, Bob (a well-known and popular lecturer) would connect with his contacts on college campuses to try to book speaking dates for me. There is a big difference between an academic presentation (either at a break-out session or a plenary talk) and solo lecturing—where everything is your responsibility. Perhaps I’d been successful as a speaker at academic conferences, but Bob’s standards and requirements were much more demanding. The college students to whom my lectures would be presented did not have a scholarly background in my specialties. I would need to develop and present general ideas. I would have to speak clearly, without jargon, if I wanted to convey my theories on the causes and meanings of political violence. Bob was optimistic: he pushed forward with confidence, and took me along with him. He believed my ideas were important and was convinced that, with the proper training, I’d be able to convey my research findings and concepts. Our sessions together were invaluable, as was the promotional piece that we developed. I’d given over 50 presentations at academic conferences throughout the country. But now I had the opportunity to focus upon—crystallize—my central themes. The first three pages of the package are scanned above, just as they appeared in the January 2003 promotion piece. I’d like to comment on the themes presented in this package, ones that I continue to develop and present. The title of the package is WHY? There is a tendency for historians—and others—to “take for granted” the extraordinary political events that characterized the 20th century. By posing the question “Why,” I’m bracketing these events, taking them out of the realm of the self-evident. Just because a certain form of behavior has occurred with great frequency throughout history, doesn’t mean that we understand it. Actually, we don’t understand what war iseven though we imagine we do. The subtitle of the package, “Civilization and Self-Destruction,” suggests two things. First, that political violence is undertaken in the name of the ideals of civilized societies. The idea that warfare manifests “primitive (or primate) aggression” is obsolete. War is intimately bound with civilizational ideals. It is in the name of our sacred ideals that political violence is undertaken. Each society is dominated by a unique ideal, and seeks to maintain this ideal at any cost. Political violence is the fury to defend an idea that lies at the core of one’s civilization. The second thing suggested by my subtitle is that warfare revolves around societal self-destruction. Given the fact that over 200 million people died in the 20th century as a result of violent political conflict, one would imagine that this conclusion—that warfare is self-destruction—would be self-evident. However, rather than looking at the fact of what occurs in warfare, historians insist upon inventing reasons. Each war has different “reasons,” but the results are the same: destruction and self-destruction. We produced 500 copies of the Promotion Piece, beautifully printed and bound. Now it was Bob Hall’s job to venture forth into the world he knew—to speak to the contacts he’d developed on campuses—and see if he could sell me as a “lecturer” presenting my unusual themes. |