| This is the first in a series of Newsletters presenting Richard Koenigsberg's theory of culture. |

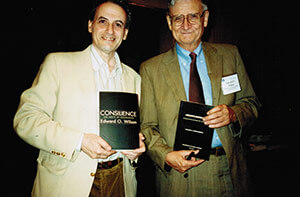

Richard Koenigsberg and Richard Koenigsberg and

Edward O. Wilson

|

In Constitutional Law of the Third Reich, Nazi political theorist Ernst Rudolf Huber wrote:

The Fuhrer is himself the bearer of the collective will of the people. In his will the will of the people is realized. His will is not the subjective will of a single man, but the collective national will is embodied within him in all its objective, historical greatness. The people's collective will has its foundation in the political idea which is given to a people. It is present in the people, but the Fuhrer raises it to consciousness and discloses it. (in Murphy 1943)

According to Huber, Nazism did not arise out of the subjective will of a single man. Rather, Hitler embodied the “collective will of the people.”

The will of a people, Huber suggests, has its foundation in the political idea which is “given to a people.” This idea already is “present in the people”; but the Fuehrer “raises it to consciousness and discloses it.” In other words, a people’s political idea is latent. The role of the leader is to manifest this latent idea—to “disclose it” to the people.

Once an idea has become conscious within a people, what follows is the will to act upon it: to turn the idea into reality. The leader’s role is to create or invent ways to activate the people’s will and to set a path that enables a people to express its collective will.

Ideology, I theorize, represents or reflects a fantasy that is shared by members of a society. This shared fantasy lies at the core—constitutes the heart and soul—of a given culture. The leader’s role is to “divine” the cultural fantasy, to give it voice.

Through his language, the leader invents images and metaphors that contain the fantasy. His role, like that of a psychoanalyst, is to “make conscious the unconscious;” to enable society’s members to become aware of a fantasy that had been hidden or latent.

In order to have a significant impact, the leader himself must be deeply mindful of his culture, that is, of its central fantasies. He processes his own fantasies (the cultural fantasy that exists within him), then develops methods for presenting or “returning” the fantasy to his people. The ideology becomes the container for a people’s shared fantasies.

Why was Hitler able to hold his audiences spellbound? Why did Germans become so excited when he spoke? Because what he said evoked something deep within many of them. People were “turned on” by Hitler’s words.

We are on the wrong track if we imagine that ideas put forth by political leaders contain, or are intended to contain, some form of “truth”; that ideas correspond to some aspect of “external reality.” The coin of the realm in politics is fantasy: the leader’s ability to express his own fantasies, and to induce or seduce others to share those fantasies. The leader presents ideas that resonate with his audience. His utterances allow followers to externalize inner states of being.

Highly successful leaders are deeply plugged in to the ideological fantasies that they put forth. No one was more moved by Hitler’s ideas more than Hitler. By virtue of his ability to share his excitement and passion, he was able to evoke a similar experience within his followers.

Ideologies function to express, contain and engage society’s members’ fantasies. The ideology becomes the modus operandi: the vehicle allowing a shared fantasy to make its way into reality (man in culture, Norman O. Brown said, is “Man dreaming while awake”). They act as a gravitational force, “pulling” fantasies into the world—capturing or sequestering the energy bound to a fantasy.

Political history occurs when a group acts upon an ideological fantasy. Hitler worked to transform his fantasy of Germany into a societal discourse. His will was the will to persuade the German people to actualize propositions contained within the ideological fantasy.

Each ideology revolves around a central fantasy. This core fantasy constitutes the heart and soul of the ideology: a sublime or omnipotent object.

History is generated in the name of these omnipotent objects. For the Nazis, this omnipotent object was “Germany.” Japan fought the Second World War for the sake of “the Emperor.” The United States participated in the First and Second World Wars for “freedom and democracy,” while radical Islamic movements revolve around “Allah.”

Historians study the numerous “reasons” why specific conflicts arise at a particular moment in history, for example, the variables that lead to the outbreak of a war. But for action to be undertaken at all, there must be a core fantasy—an omnipotent object. Without “Germany” or “the Emperor” or “freedom and democracy” there could not have been a Second World War.

To understand a particular ideology is to uncover and reveal the core fantasy. In the case of Nazism, this fantasy revolved around the idea of Germany as an actual body (politic) suffering from a potentially fatal disease, the source of which was the Jew. Hitler put himself forward as “doctor” of the German people, the man who could root out and destroy the cause of Germany’s suffering, thereby rescuing the nation and saving it from death.

For any ideology, I pose and seek to answer the question: Why does this ideology exist?

- What fantasy or set of fantasies does the ideology contain or convey?

- What methods are used by the leader to encourage members of his society to believe in and act upon the ideological fantasy?

- Why are followers willing to perform violent acts in the name of the ideological fantasy?

- What do leaders and followers hope to achieve by acting upon their society’s ideological fantasy?

Ideologies constitute modus operandi for the expression and enactment of shared fantasies. They become central within a society precisely because they allow unconscious fantasies to be expressed and articulated. They are containers for shared fantasies, driving the historical process. Unconscious fantasies enter history through ideologies.

Where Freud interpreted individual dreams and dreaming, I interpret collective dreams and dreaming, seeking to ascertain latent thoughts beneath manifest content. This is what I mean when I speak of “making conscious the unconscious in social reality.”

The Nazi revolution constituted the acting out of a dream that many people were having at the same time—a shared fantasy powerful enough to give rise to an ideology and social movement. Dreaming this dream most deeply, Hitler was able to articulate the Nazi fantasy. To know why Nazism achieved popularity, one seeks to determine precisely what Hitler said that caused Germans to rise to their feet and shout "Heil Hitler."

I theorize that a necessary condition for the espousal of an ideology within a society is the existence of an unconscious fantasy shared by group members. The ideology is a cultural creation or invention permitting a shared fantasy to manifest as social reality.

It is through the medium of an ideology that a shared fantasy becomes part of the world. An ideology is believed, embraced and perpetuated—it achieves status and power as an element of culture—insofar as it resonates with a fantasy and permits this fantasy to be activated upon the stage of society. |