|

|||

Commentary by Professor David L. Weddle

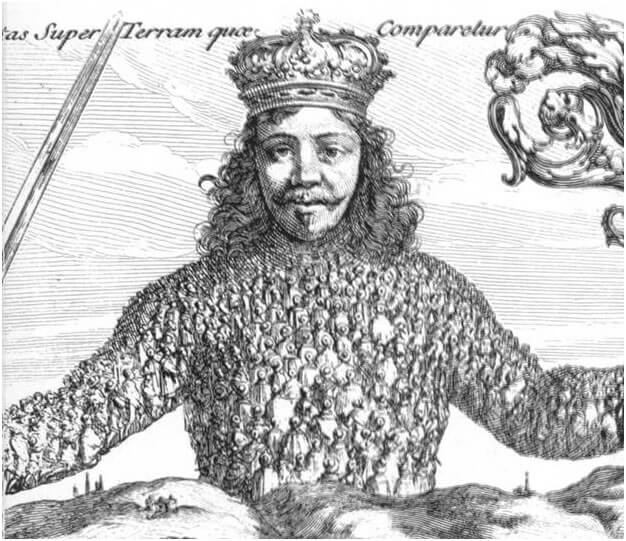

It may be worth recalling a point about this image made by Timothy Beal in Religion and Its Monsters (Routledge, 2002) that the tiny individuals who comprise the body of the supreme authority, by relinquishing their wills to it, all face inward. That is, they have no independent view of the landscape over which the religio-political leader rules. In exchange for the security of his absolute power, they sacrifice their personal agency and right of judgment. In light of later Enlightenment ideals of individual liberty, this image can be read, retrospectively, as an ironic symbol of the cost of submitting as the “body politic” to a single supreme head. |

|||

COMMENTARY ON WEDDLE by Richard A. Koenigsberg

David Weddle observes that the tiny individuals who comprise the body of the supreme authority all face inward and have “no independent view of the landscape.” In exchange for the “security of absolute power,” they “sacrifice their personal agency.” The sense of security follows from the fantasy of bodily union with the sovereign. This is a symbiotic fantasy: the experience of no separation between subject and king. The sovereign cannot exist without the people who constitute his body; the people cannot exist without the King who constitutes the head of their body. Hitler declared to his youth (September 8, 1934), “You are flesh from our flesh and blood from our blood.” Nazism represented the fulfillment of Hobbes’ fantasy. The ideal Nazi would have no independent will but would be bound to Hitler’s body. “Obedience” does not require convoluted social psychological explanations. Obedience derives precisely from this psychosomatic fantasy of being bound to the body of the sovereign. If the subject imagines that he is bound to an omnipotent body, how can he be other than obedient? As Weddle points out, the fantasy of submission to a body politic contradicts the “Enlightenment ideals of individual liberty.” So here we have two primal fantasies at the heart of Western political culture. On the one hand, the idea of liberty, rationality and reason: the human being as a conscious actor who freely chooses paths of action. On the other, the profound desire to fuse with a sovereign: to experience the pleasure of being bound to a body conceived as omnipotent. Political “rebellion” grows out of the experience of attachment to the body of the sovereign as oppressive. Whatever the joys of omnipotence, it is not pleasant to imagine oneself bound to the body of another being. Rebellion represents the struggle to liberate oneself from attachment. Freedom is equivalent to separation. |

PSYCHOSOMATIC ROOT OF WESTERN POLITICAL CULTURE |

|

|