| About the Author

Dr. Pingchao Zhu is Associate Professor of History at the University of Idaho. Her teaching and research areas include the Korean War Armistice Talks, US-China relations, Chinese wartime culture, regional warlords, and East Asian political and cultural developments.

Americans and Chinese at the Korean War Cease-Fire Negotiations 1950-1953

Author: Pingchao Zhu

Publisher: Edwin Mellen Press

Format: Hardcover

Published on: 2001

ISBN-10: 0773474242

Language: English

Pages: 260

For information on purchasing this book through Amazon, click here.

Description: This study applies the most recently released government documents from Russian and Chinese archives and updated English scholarship to the analysis of both US and Chinese diplomatic activities. |

|

A Note from the Editors at

Library of Social Science:

Dr. Zhu’s essay and accompanying photos provide a unique perspective: allowing Americans to understand how China conceived of and experienced the Korean War. Below is a condensed version of the entire essay, which appears here.

Below her essay are photos of Dr. Zhu’s visit to a ceremony in South Korea commemorating the 50th anniversary of the War. |

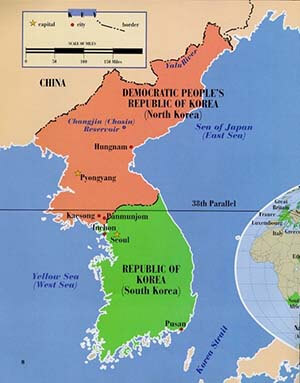

China entered into the Korean War at a critical historical moment: the new Communist regime had just celebrated its first anniversary in October 1950. In military strength and industrial capacity, China was no match for its opponent, the well-equipped and supplied United Nations Command (UNC) under the United States military command leadership. What China could rely on was its massive manpower and political propaganda — entrenched in the Marxist doctrine of anti-imperialism and internationalism.

On October 8, 1950, Mao Zedong — in the name of the Chair of the Chinese People's Military Commission — issued an executive order organizing the army of the Chinese People's Volunteers (CPV) to enter the Korean War on the side of North Korea. Mao elaborated on the nature of China's decision to enter into the Korean conflict: “To assist [North] Korean people's liberation war, to resist the aggression of the American imperialists and their running dogs, and to protect the interests of the [North] Korean people, the Chinese people, as well as countries in Asia.”

|

Chinese military forces crossing the

Yalu River, October 1950 |

The Chinese government strove to galvanize its population into the belief that they were fighting a just war. Mao had always paid special attention to the role of political motivation for war. “It is of utmost important to let our military and people know the political purpose of the war,” Mao emphasized. “It is highly necessary to explain to every soldier and every citizen why the war is to be fought, and how the fighting is related to them.”

The war waged by China was not simply portrayed as a conflict in Korea: it was dubbed by the Chinese authority as kangmei yuanchao, baojia weiguo, “the War to Resist American Aggression and Aid [North] Korea,” “Defend Homeland and Protect Our Country.”

|

U.S. Infantry troops at Taejon railroad

station, July 1950 |

When the People's Daily carried articles on U.S. bombing of China's border cities, they showed bloody bodies and burned houses, making the war in Korea personal to the Chinese people. “American imperialists have brought the war to the Yalu River border,” the editorial from the People's Daily claimed. “Until the war on the Korean Peninsula ceases, there will not be peace along the Yalu River.” Instantly, the fundamental interest of the Chinese people came to be tied closely to the war in Korea: the only way to resolve this crisis was to send in China's support to the Korean people.

War demands commitment and sacrifice. The Communist authorities enshrined the ideal of revolutionary heroism into their wartime culture of patriotism and sacrifice. According to Communist theory, revolutionary heroism is the opposite of individual heroism. While the former is focused on individual fame and self-interest, the former emphasized daring to fight and eventually give one's life for the revolutionary cause one believes in — and to make sacrifices for the public interest and masses.

In 1945, Mao expounded on the features revolutionary heroism: “This army embraces the spirit of moving forward unstoppably and of overwhelming all enemies, but never to be overcome. Under any circumstance, as long as there is one man left, he must fight to the end.” Since the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921, the Communists had upheld the tradition of revolutionary martyrs who had laid down their lives for the cause, and for the brighter future of a Communist China.

These martyrs, according to Zhu De, one of Communist China's most prominent military commanders, “would not only sacrifice part of their own interests, but also their own lives without hesitation, for the sake of revolutionary interest and needs.” This was the essence of revolutionary heroism: one person's sacrifice for millions of other peoples' lives, and for the nation's security. The Korean War provided a great opportunity for every Chinese, soldiers or not, to embrace the spirit of revolutionary heroism.

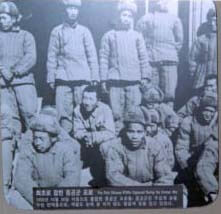

Photos showing the

Chinese People's Volunteers at war

(Korean War Museum, Seoul) |

|

|

|

| CPV soldiers getting their rations |

CPV troops charging forward |

CPV prisoners of war

under the UNC custody |

Wei praised the bravery and virtue of the CPV soldiers — in a fashion similar Pericles in his funeral oration to the Athenians during the Peloponnesian War in the 5th century B.C. Wei's extolment of the CPV soldiers seemed to prove the unlimited human power sustained by revolutionary heroism, when one CPV company fought to kill some 300 enemies — while suffering heavy casualties by overwhelming enemy fire power from air bombing, tank and artillery, flame thrower, and strong frontal assaults. The CPV Company managed to hold onto the position until the arrival of reinforcement.

This ancient idea that warriors, “because of their godliness and virtue, can vanquish strong opponents,” was shared by many. One historian noted that “the Christian crusaders counted on it. Jihad, Islam's conception of a holy war, is based on it. The [Japanese] Samurai believed it. So did the Nazis.” In the case of the CPV forces in Korea, the sentiment of the kangmei yuanchao movement empowered the CPV soldiers to believe they were fighting a just war for a just cause, which was invincible.

Mao's strategy in proving “man can beat weapon” lay in his using at least four times larger, if not more, in number of troops, and 1.5 to two times bigger the fire power than that of the enemy's — in order to eliminate them. The concept of “human wave” was born. As a result, more martyrs were in the making, and more sacrifices would be added to the national glory and international stardom.

In war, death can transcend to a higher realm of nobility. When death casualties of the CPV soldiers were reported back home, the nation and the people seemed to have little time to grieve. The authorities wanted everyone at home to “turn grief into strength, sorrow for the loss of loved ones into hatred toward the American imperialism.” Sacrifice for the Chinese nation and world peace was a glorious deed. “As a prideful CCP member,” one anonymous CPV soldier wrote the night before he was to die defending the hill top, “[I] must give my life…for the victory…for my motherland…”

One historian whose research focused on heroes in Nazi Germany commented, “Death in battle not only guaranteed eternal life for the martyrs, but also acted as a resurgent life force for the Fatherland. Death in combat took on the ennobling force of a sacrament.” Communist revolutionary heroism ensured eternal life in propaganda for those who died for the revolutionary cause. Both Huang Jiguang and Qiu Shaoyun pledged before going into battle that they were willing to “give their lives for the victory.”

Now they had achieved just that, dying a heroic death fighting the most powerful country in the world, the United States. The state apparatus rigorously created an account of the heroism of the CPV soldiers — who lived for the life of their motherland, and died for the peace of the Korean people. In life they were part of the “most beloved,” and in death they joined the immortals.

Mao and his elder son, Mao Anying, Mao and his elder son, Mao Anying,

who died in the American bombing of Korea |

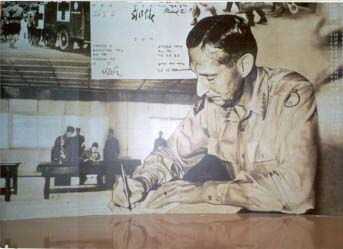

General Clark signing the Korean War

Armistice Agreement in July 1953 |

A very special martyr was among some 180,000 souls buried in North Korea. He was Mao Anying, the eldest son of Mao Zedong, who died in an American air raid in November 25, 1950 while working in the CPV headquarters in North Korea. Upon hearing the news, Mao's response was calm but solemn:

In war there must be sacrifice. So many CPV soldiers have given their lives already. As a proletarian fighter and a CCP member, Anying has done his duty. He is an ordinary soldier of the CPV. His death should not be made a big issue just because he is my son. Why can't a son of the CCP chair be making sacrifice for the common cause of the Chinese and Korean peoples?

The ending of the Korean War — with an armistice and return of the CPV POWs — seemed to have cast a spell on the sacrifice and devotion China made in the Korean War. Throughout the war, Mao and the Chinese authorities made good use of the propaganda apparatus to promote revolutionary heroism, and placed individual CPV soldiers' deaths within the context of homeland security and world peace, which demanded sacrifice to safeguard a nation's survival. China's heroes were given an active role — as they walked toward death with courage and vigor.

There was no doubt that the CPV soldiers truly believed in why they were fighting and what they were fighting for in Korea. Death seemed more justifiable than life — to achieve the title of revolutionary hero. Retrospectively, the Korean War occupies a special place in Communist China's history. Sending millions of China's best to fight in Korea was no easy decision for Mao and the new leadership to make.

|